The purpose of the "Spiritual Successors" entries is to figure out one thing about an artist/group: will another similar artist ever come along after that achieves similarly to the original group.

This requires a few things:

1. Spiritually similar. Are they both trying to achieve the same thing? This could be from being highly political to highly introspective/spiritual. As long as they are the same or similar, then we can consider the later the successor of the former.

2. Following from 1., but also of import: being a spiritual successor does not mean they have to be stylistically similar...not at all. For one, being overly restrictive limits options, and two, the nature of music has been dynamic, with different things "in" and different things "out," which means that what's good one era is not good in another (ahem, punk). To apply an analogy, if you expect yourself to be reincarnated, you wouldn't be reincarnated as "yourself," no? You would be reborn in a different vessel and do things in a unique way.

3. Similar music "methodologies." This mostly concerns the approaches that both the predecessor and the follower take to the music. Are they both generally eclectic and incorporate all sorts of elements into their music? Or do they both prefer to ply the trade they have perfected? The general consensus is here that the sorts of spiritual successor strains will be of the "eclectic" variety; most artists tire of continually "plowing their own field" (to use the vernacular of a bygone era) and choose to try something new, or to at least incorporate something new.

That being said, this does not imply that there will always be a spiritual successor for a group before. The Beatles are a good example of such. While perhaps I can discuss this at a later date and prove that no group has been able to recreate the Beatles with any degree of success, the point to make is that the Beatles were so good, so unique, so diverse in what they achieved that no artist has ever come close to the creative burst that powered their years. It really was a perfect storm for them.

Now that I've outlined the guidelines for the "Spiritual Successors" series, let's begin...

---------

The Clash were regarded as "the only band that matters," as said by pretty much everyone. Roaring along in the 1970s, they were the distinctly political side of punk. With anthems such as "White Riot" which promoted action (i.e. violence) and even the dirges such as "Straight to Hell" (hint...this song will come into play later), they lamented their lot in life much like the rest of the punk movement, but what separated them from the rest of the chaff was their willingness to try to change it.

And they were simply good. When you put on the Clash and hear "Clash City Rockers" explode out of your speakers for the very first time, the riff is quite simply embedded in your head for the rest of your life. In typing that last sentence, the riff just came bubbling out of the blue, a sort of semi-conscious recall that implies a sort of timelessness to their work (no matter how dated the punk movement became). And yes, before purists cry out, when I refer to "Clash City Rockers" playing from the Clash, I am, in fact, referring to the U.S. version of the record that came out post-Give 'em Enough Rope, as the U.K. version was never available in the United States...and, well, I'm from the United States.

Then there was their seminal record: London Calling. There is no need to defend the record. But it's important to point out how eclectic the record is in comparison to their previous ones (and to basically most records in existence). They started incorporating reggae, they dabbled in parlor jazz, noisy blues-rock, and the like. Nothing was off limits, because punk was about "no limits," not the power chord. The pop of "Train In Vain." The sinister crawl of "The Guns of Brixton." The apocalyptic march of the title track. Need I go on?

While perhaps Sandinista! was a strange choice, it pushed the boundaries of what "eclectic" meant. If you want an explanation (and don't want to trudge through 3 LPs, which at times is hard to manage), then look no further than the children's chorus version of one of their more famous "old school punk" songs, "Career Opportunities." It was already a highly political message in its first form, and given the new dressing, gained an especially vicious edge to its commentary.

As I said earlier, it was their political stance that separated them from the rest, the men from the children (so to speak). No one dared to get explicitly political, because there was always a sense of fear given that if you were outside the box, you would never get anywhere. Of course, given the Clash, getting anywhere was not really the issue, because they started nowhere, so somewhere was better than there. But most of all, they were simply bold enough to insert themselves into the political issues of the time (see the title of their fourth record: Sandinista! and you see).

So we see two trends from the Clash: while at first content to stew their own pot, they later became quite eclectic in their approach. They were also highly political (and generally great people to boot, but that's a separate entry), unafraid to confront their lot in life, and to make a stand and send a message. Is there anyone who, perhaps, can be viewed as their spiritual successor? I say yes. It is, in fact, this artist/person:

M.I.A., as she's known, is essentially a rapper from London, I believe, who traces her roots back to Sri Lanka. Her two records, Arular and Kala, are dizzyingly eclectic, with noises and sounds, thick and dirty beats flying in and out, all tied together by her verses. Stylistically, the two are far apart. Rap vs. punk, and you see a stark contrast, an uncrossable rift between the two. But neither artist treated their respective genres as a chafing categorization, but moreover a springboard to something new. The Clash incorporated reggae primarily, alongside almost every other genre into their songs, while M.I.A. has been fearless in her sampling of tracks that make her songs unmissable (in fact, "Straight to Hell" was sampled in M.I.A.'s "Paper Planes," which was her mainstream hit...it all makes sense now, no?). While the methods of each artist's eclecticism are different, that seems to be a product of the dynamic state of music, rather than an inherently different approach to their music.

While she does not dedicate herself to political material (not even the Clash did that), the amount of it is staggering and is likely comparable to that of the Clash. Of course, M.I.A. has probably been better off than the Clash have ever been in a financial sense, but M.I.A., like the Clash, took one issue to heart (the Clash's was essentially the poor standard of living in London, though usually more general than just London). Her core issue relates to her ancestry in Sri Lanka, specifically concerning the Tamil uprising and the conflict that enveloped the region (and, I would hazard to guess that it's probably not as over as some people like to think).

The comparison seems fairly apt. Both highly political, both highly eclectic. While perhaps I have not treated the "issue" (though I don't consider a faux-academic examination of an aspect of rock music to be much of a pressing "issue," much less an actual "issue") with as much depth as it may deserve, I think in general, the point has been made and brought up for discussion.

Also, M.I.A.'s new track, "Born Free," is ridiculously awesome, which partially inspired me to write the first entry to this series (I had the idea for the series already, just hadn't gotten around to it yet).

Sunday, April 25, 2010

Monday, April 12, 2010

Lost Albums

Since it's been a long time, this entry is like a "lost entry" and so I feel like it's fair to discuss "lost albums":

Lost albums in rock lore are pretty much legendary. Sometimes they surface soon. Sometimes they surface much later. Sometimes they don't. Sometimes it's just a bunch of tapes that are compiled later, or sometimes they are completely re-imagined from the ground up. Here's a look at the more famous ones (and some personal favorites)

Cases in point:

1. The Beach Boys - Smile

This is probably the most fabled one of the "lost albums" bunch. This was supposed to be Brian Wilson's "teenage symphony to God." It was supposed to eclipse, yes, eclipse Pet Sounds. How the hell is that supposed to happen? Make another record more perfect than one of the most perfect pop records ever? But for one reason or another, this album became lost. Brian Wilson went a bit bananas, battling various sorts of not-very-good mental states, group conflict, and the ilk, all causing the project to fall to the wayside. This record was bootlegged heavily, with fights all over, trying to compile the definitive statement regarding Smile. But all that was, for most intents and purposes, settled in 2004 when Brian Wilson, finally returning to peak form, completed the record (now with strange capitalization schemes) we all know and love as SMiLE:

Who knows if this is as good as the original was supposed to be? I prefer to not think about that and just rejoice in the perfect pop that the record is. In some sense, with age changing Brian Wilson's voice, the songs take on a new meaning, one of wizened (and therefore sly) reflection rather than the youth and innocence that so starkly characterized Pet Sounds...but it gives the record a second meaning. And as I said, it's neither here nor there, as the album is as good as it gets (and I consider it one of the best entries of the previous decade).

2. Bob Dylan & the Band - The Basement Tapes

Another ubiquitous "lost album" that found its way to shelves when its commercial power was realized. And what a powerful set of songs this is. Down home folk, rolling blues, and the like, all casually tossed off as if recorded over breakfast or during a brief period of downtime in the middle of the day. The songs ooze cool, nonchalance, a folksy wisdom that only Bob Dylan and the Band have been able to replicate (the Band moreso than Bobby D, but I think Bob Dylan made the conscious choice to avoid the same path).

Dylan was recovering from a motorcycle accident that had nearly ended him, and just recording by himself and the Band. No one knows the particulars and the details, and various forms of the set of tapes exist. In some ways, this album is still lost because there is no definitive statement on this time period outside of either going whole-hog with the entire complete set of the Basement Tapes (something like a five-disc set with at least three takes of most tracks) to the very short two-disc version missing some tracks. The debate will always continue, and I honestly think Bob Dylan prefers it that way.

3. The Velvet Underground - VU

So perhaps this not necessarily a straight up "lost album" like Smile or just a smattering of tapes all thrown together like the Basement Tapes (despite similar origins), but the record has been compiled from rough mixes and demos into a finely tuned, muscular beast. Mostly from the end of their career at MGM records, these tracks were supposed to be the last record on their deal there, but for reasons no man can fathom, they were unceremoniously booted from the label. These demos and rough mixes were recorded for MGM before they left and recorded Loaded, but these tracks were left undiscovered until the 1980s when the Velvet Underground underwent a bit of a renaissance in terms of sales and opinion.

The record may seem to be a sort of outtakes and demos compilation that seems pre-solo Lou Reed more than anything else, but the (obvious) secret is that Lou Reed's best outfit for performing his songs had been and will always forever be with the Velvet Underground (i.e. John or Doug, Moe, and Sterling). So yes, "Andy's Chest" shows up on Transformer, but the lazy beat on his solo work is replaced by a bouncing giddy-ness here that is superior. "Stephanie Says" became "Caroline Says II" on Berlin, but to be frank, "Caroline Says II" is not great whereas "Stephanie Says" is perfect...a slightly cruel, very melancholy ballad that was likely directed at their manager at the time.

The record was prepared with as much care and consideration as, to a great extent, any other Velvet Underground record. I consider it more or less canon, placing it in its recorded-chronological place rather than its release-chronological place (i.e. between the Velvet Underground and Loaded rather than post-Loaded). The urge to wax more eloquent on this record is tempting, but I will prevent myself on doing so because it's quite contrary to the point of this entry.

There are other examples, both great and not so great, but given these case studies (Smile being the famous one, the Basement Tapes being the pretty famous one, and VU being the personal favorite), it is clear that at some point, a lost album will always be found. As the myth indicates, "all that wander are not lost," and perhaps the idiom applies to a great extent for records in rock music.

Lost albums in rock lore are pretty much legendary. Sometimes they surface soon. Sometimes they surface much later. Sometimes they don't. Sometimes it's just a bunch of tapes that are compiled later, or sometimes they are completely re-imagined from the ground up. Here's a look at the more famous ones (and some personal favorites)

Cases in point:

1. The Beach Boys - Smile

This is probably the most fabled one of the "lost albums" bunch. This was supposed to be Brian Wilson's "teenage symphony to God." It was supposed to eclipse, yes, eclipse Pet Sounds. How the hell is that supposed to happen? Make another record more perfect than one of the most perfect pop records ever? But for one reason or another, this album became lost. Brian Wilson went a bit bananas, battling various sorts of not-very-good mental states, group conflict, and the ilk, all causing the project to fall to the wayside. This record was bootlegged heavily, with fights all over, trying to compile the definitive statement regarding Smile. But all that was, for most intents and purposes, settled in 2004 when Brian Wilson, finally returning to peak form, completed the record (now with strange capitalization schemes) we all know and love as SMiLE:

Who knows if this is as good as the original was supposed to be? I prefer to not think about that and just rejoice in the perfect pop that the record is. In some sense, with age changing Brian Wilson's voice, the songs take on a new meaning, one of wizened (and therefore sly) reflection rather than the youth and innocence that so starkly characterized Pet Sounds...but it gives the record a second meaning. And as I said, it's neither here nor there, as the album is as good as it gets (and I consider it one of the best entries of the previous decade).

2. Bob Dylan & the Band - The Basement Tapes

Another ubiquitous "lost album" that found its way to shelves when its commercial power was realized. And what a powerful set of songs this is. Down home folk, rolling blues, and the like, all casually tossed off as if recorded over breakfast or during a brief period of downtime in the middle of the day. The songs ooze cool, nonchalance, a folksy wisdom that only Bob Dylan and the Band have been able to replicate (the Band moreso than Bobby D, but I think Bob Dylan made the conscious choice to avoid the same path).

Dylan was recovering from a motorcycle accident that had nearly ended him, and just recording by himself and the Band. No one knows the particulars and the details, and various forms of the set of tapes exist. In some ways, this album is still lost because there is no definitive statement on this time period outside of either going whole-hog with the entire complete set of the Basement Tapes (something like a five-disc set with at least three takes of most tracks) to the very short two-disc version missing some tracks. The debate will always continue, and I honestly think Bob Dylan prefers it that way.

3. The Velvet Underground - VU

So perhaps this not necessarily a straight up "lost album" like Smile or just a smattering of tapes all thrown together like the Basement Tapes (despite similar origins), but the record has been compiled from rough mixes and demos into a finely tuned, muscular beast. Mostly from the end of their career at MGM records, these tracks were supposed to be the last record on their deal there, but for reasons no man can fathom, they were unceremoniously booted from the label. These demos and rough mixes were recorded for MGM before they left and recorded Loaded, but these tracks were left undiscovered until the 1980s when the Velvet Underground underwent a bit of a renaissance in terms of sales and opinion.

The record may seem to be a sort of outtakes and demos compilation that seems pre-solo Lou Reed more than anything else, but the (obvious) secret is that Lou Reed's best outfit for performing his songs had been and will always forever be with the Velvet Underground (i.e. John or Doug, Moe, and Sterling). So yes, "Andy's Chest" shows up on Transformer, but the lazy beat on his solo work is replaced by a bouncing giddy-ness here that is superior. "Stephanie Says" became "Caroline Says II" on Berlin, but to be frank, "Caroline Says II" is not great whereas "Stephanie Says" is perfect...a slightly cruel, very melancholy ballad that was likely directed at their manager at the time.

The record was prepared with as much care and consideration as, to a great extent, any other Velvet Underground record. I consider it more or less canon, placing it in its recorded-chronological place rather than its release-chronological place (i.e. between the Velvet Underground and Loaded rather than post-Loaded). The urge to wax more eloquent on this record is tempting, but I will prevent myself on doing so because it's quite contrary to the point of this entry.

There are other examples, both great and not so great, but given these case studies (Smile being the famous one, the Basement Tapes being the pretty famous one, and VU being the personal favorite), it is clear that at some point, a lost album will always be found. As the myth indicates, "all that wander are not lost," and perhaps the idiom applies to a great extent for records in rock music.

Wednesday, March 17, 2010

Rest in Peace, Alex Chilton

December 28, 1950 - March 17, 2010

But guns they wait to be stuck by, and at my side is God

And there ain't no one goin' to turn me 'round

Ain't no one goin' to turn me 'round

And there ain't no one goin' to turn me 'round

Ain't no one goin' to turn me 'round

At this point, I would like to forward you all to this blog entry here for my entry on Big Star, which is what Alex Chilton was best known for. And then this is the part where you go put on some Big Star, and quite frankly, it really doesn't matter which record you put on because they're all fucking masterpieces, and Alex Chilton was (and will forever be) the fucking man. Everyone knew Big Star was the real deal, one of the few consummate bands of the entire history of rock and roll. It is virtually impossible to compete with what Big Star achieved.

I'm going to let other people say these words:

Big Star's "impact on subsequent generations of indie bands on both sides of the Atlantic is surpassed only by that of the Velvet Underground."

-Jason Ankeny, allmusic

"We've sort of flirted with greatness, but we've yet to make a record as good as Revolver or Highway 61 Revisited or Exile on Main Street or Big Star's Third. I don't know what it'll take to push us on to that level, but I think we've got it in us."

-Peter Buck, R.E.M.

---

"I'm constantly surprised that people fall for Big Star the way they do... People say Big Star made some of the best rock 'n roll albums ever. And I say they're wrong."

Let's be frank...Alex Chilton was way off the mark. Big Star made some of the best rock and roll albums ever. He's either way too modest to admit it or way too much of a genius to see it. I choose both.

But the Replacements, I think, said everything about Alex Chilton and the work he'd done with Big Star (and, truthfully, in general) the best:

"I never travel far without a little Big Star."

Rest in peace, Alex Chilton.

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

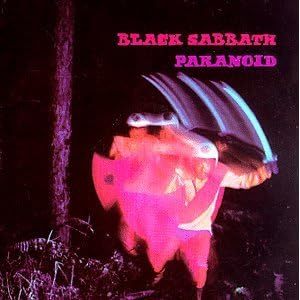

Record of the Moment: Black Sabbath - Paranoid

You may say, "WOAH THERE, what happened to this guy? He now listens to heavy metal?" The answer is "This record," and this record only. Let's be honest, this record isn't heavy metal in the modern sense. It's like Led Zeppelin but jammier and heavier. But at the time, that was way heavy metal. No one really dared to go that heavy before.

But that's not the point. This is a one-of-a-kind record. I'm no expert on metal, but sources I've gathered say that it simply is one of the finest, ever. I don't listen to metal at all, but the songs on this record are pretty sick. "War Pigs" is, according to a friend of mine who's more metal-inclined than I am (though he is of the Grateful Dead vein more than anything else), the best heavy metal song of all time, and one of those flawless rock songs. The second I can definitely agree with. "War Pigs" is both a flaming indictment of warmongers in power and a maelstrom of sheer muscle and power. Iommi's guitar charges along, while the rest of the band acts like they are, perhaps, dogged on by the hounds of hell.

I know that heavy metal and Black Sabbath in particular gets a rap as Satanist, but look at these lyrics, from "War Pigs":

"Now in darkness world stops turning

As the war machine keeps burning

No more war pigs have the power

Hand of God has struck the hour

Day of judgment God is calling

On their knees, the war pigs crawling

Begging mercy for their sins

Satan laughing spreads his wings"

What is Satanist about that? There really isn't a whole lot of Satanism going on there. It really is a whole bunch of talk about the end of the times, which is not very Satanist to me. Especially when the song calls on the Hand of God to render judgment unto the war pigs. Of course, I'm not really familiar with later Black Sabbath, and we all know Ozzy Ozbourne is a loony, so I could be wrong. But back then it doesn't seem like that.

Other dudes like Christgau make fun of the hokey lyrical themes that Black Sabbath use, such as all the sci-fi, horror-film talk, but in the end, it's the same application just of a different theme. In the sense that, for example, David Bowie plumbed the Ziggy imagery. It's a little different, but you get the gist. If all the faux-horror and sci-fi imagery was not artfully applied to the music they had, I'm sure Black Sabbath would deserve that rap. But once, again, look at the above lyrics. They're not too shabby, are they? Look to basically the first side of the record and prepare to have your face blown off.

But yet, it is heavy metal. I'm not going to put this on a whole lot. But it is a great record. It shows a definite Zeppelin influence in the same sense that both adapted blues styles and played it as heavily as possible. The guitar work on the record is killer, the bass and drums are tight, and Ozzy sounds a bit like Iggy Pop, but in a much different mindset. Invariably, from what I can tell, the Black Sabbath strain of heavy metal is dead.

This is my discussion on the genre itself. Black Sabbath, while still trying to sound demented in only the way heavy metal can, always seemed to base itself a bit off of the Zeppelin model, relying on old blues forms, a stiff pair of balls, and a bunch of gusto to make the songs heavy metal. While certainly Iommi shows his chops a whole lot, it's not exactly slavish in the way metal sounds now. He doesn't take a whole lot of solos on the record, mostly just chilling and creating a mean rhythm track for Ozzy.

But look at metal now. It has sort of degenerated into a bunch of people trying to outplay one another, becoming a showcase of technical skill rather than an art form related to the spirit of rock music. Which is why I consider modern metal disowned from the rock tradition. Metallica was the rare band, from what I can tell (another friend of mine is much more Metallica-inclined than I am), that straddled the line between embracing the tradition while still sort of being as "technically excelling" as possible.

But all these phonies running around trying to outplay one another miss the point of rock music. I would make the claim that they actually are moreover descendants of the classical music tradition, where technical displays are actually encouraged and written into the music. Because, to be honest, classical music is dying out. Hardcore. It pains me to admit it (having been an orchestra dork in high school), but it's true. It's dying. And somehow, a bunch of metalheads are the ones concerned enough with the extremely technical sides of music to save it.

Sorry for the divergence. Seriously, this is a wicked record. And I mean "wicked" in the sense that it's good, not in the Satanist sense, mind you.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Ragged Glory: the Art of the Double-Album

Every artist has thought about making a double album. Few have done it, and even fewer have even met any sort of success doing it. Why has the double album been so appealing, and what determines the success (or failure) of a double album?

I think that the reason why the double LP has been so popular is that it gives artists a great amount of artistic lenience with what they want to pursue. If they don't have a particular direction in mind, they can make a double album going every sort of direction! It's actually a pretty convenient solution. This sort of smorgasbord approach is likely the most common approach when it comes to double albums: there's too much to cut out to make a single LP, either due to egos (i.e. the Beatles, perhaps) or because maybe there's just too much good material there (also i.e. the Beatles). Basically, the problem (too much stuff) is resolved by keeping the problem (too much stuff? keep it)...like throwing everything and the kitchen sink at a problem. Sometimes, the extra space is needed to expound on an album concept (closely intertwining with the art of the concept album), like the Who's Tommy. This last iteration is much less common, but its validity cannot be dismissed.

It's necessary to break the double-LP into two categories because each has to be graded on very different forms. While all albums should still follow the general criteria I outlined much earlier, double-LPs gain some leniency in some quarters but generate some extra rules in return. The first, which we'll call the "sprawl" double-LP:

1. The "sprawl" double-LP must cover enough ground. If it doesn't, it's what we'll call the "under-sprawl" double-LP. If you do not have enough variation to cover two LPs, then don't do it. It may be bearable to go through the same shtick for one LP, but two is overkill. Simply put, you have enough room to tinker around, so do it! Don't waste the space on the same genre the whole time!

2. That being said, there is such thing as "over-sprawl," where you just cover way too much ground without stylistic focus and a core to what you're going for. This is typically the worst version of the double-LP, too much of everything, not enough of something. The "over-sprawl" double LP uses the extra space as room for experimenting. Do that in the studio! Don't release that if it's only use was to mess with that random studio effect! You're hurting the album in all quarters by going with the "over-sprawl" approach!

3. All Criteria established in my Mission Statement still apply, no questions asked. However, given the nature of a double-LP, flow can oftentimes be broken up LP by LP, or side by side, depending on the record. That rule requires the "double-LP exception," which I actually hinted at there.

The concept double-LP has a different set of criteria:

1. Does the concept deserve to be on two LPs? Is it really that expansive to require that second LP? Do you really need an extra 40 minutes to expound on your hero's walk from his garden to the grocery store? Probably not. But do you need an extra 40 minutes to talk about key events, themes, and motifs? If yes, then you need the second LP! Yes, this can apply to instrumental segues on a double-LP, which oftentimes are very capable of providing respite or a connecting piece to another section of a record.

2. Are all tracks thematically relevant? Related to the above rule but sort of distinct. It can musically fulfill the concept, or lyrically fulfill the concept, but if it doesn't, throw it out! It doesn't belong at all! This is basically a corollary to the "over-sprawl" rule with a specific application to double-LPs.

3. Same as the "sprawl" double-LP rule. Everything still applies. But with a concept double-LP, there simply is less room for flow problems, and flow separation (or lack thereof) becomes a much bigger issue.

Given the criteria, it's simply quite easier to craft a good "sprawl" double-LP than it is to craft a good "concept" double-LP. Here's a list of masterful double-LPs, and it's actually quite short (no order):

The Beatles - The Beatles

The Rolling Stones - Exile On Main St.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Electric Ladyland

The Clash - London Calling

Led Zeppelin - Physical Graffiti

Bob Dylan - Blonde On Blonde

Bob Dylan and the Band - The Basement Tapes

Miles Davis - Bitches Brew

The Who - Tommy

Derek and the Dominos - Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs

Bruce Springsteen - The River

Sonic Youth - Daydream Nation

The Minutemen - Double Nickels on the Dime

It's by no means the definitive list, but it's a good compilation of the good stuff when it comes to double-LPs. Each record I listed I would probably consider a must-listen at some point. Yes, it's going to be a full 70-90 minutes of your life to work through it, but I'll be damned if it won't be a 70-90 minutes very, very well spent. While it's definitely hard to apply my criteria to the Miles Davis record, really...who doesn't love that record (except the traditional jazz cats)?

I did want to mention what I consider to be the outer frontier of the double-LP: the triple-LP. Until this week, I was only able to think of two musicians who had even dared to compile a triple-LP: George Harrison and the Clash. And, coincidentally, they're both ridiculously good records...

George Harrison - All Things Must Pass

The Clash - Sandinista!

The only person since then that had even dared to venture into that territory just joined the field this week - Joanna Newsom - with the record Have One On Me. Maybe it should have been called Have Two On Me, because there's two extra LPs (and in this instance, yes, in the LP sense because the album spans over three LPs...meaning it is two hours long). Time will only tell if Joanna Newsom joins the ranks of the Clash and George Harrison as the only people to ever successfully produce a triple LP. Even daring to do it deserves many accolades...at least in my opinion.

I think that the reason why the double LP has been so popular is that it gives artists a great amount of artistic lenience with what they want to pursue. If they don't have a particular direction in mind, they can make a double album going every sort of direction! It's actually a pretty convenient solution. This sort of smorgasbord approach is likely the most common approach when it comes to double albums: there's too much to cut out to make a single LP, either due to egos (i.e. the Beatles, perhaps) or because maybe there's just too much good material there (also i.e. the Beatles). Basically, the problem (too much stuff) is resolved by keeping the problem (too much stuff? keep it)...like throwing everything and the kitchen sink at a problem. Sometimes, the extra space is needed to expound on an album concept (closely intertwining with the art of the concept album), like the Who's Tommy. This last iteration is much less common, but its validity cannot be dismissed.

It's necessary to break the double-LP into two categories because each has to be graded on very different forms. While all albums should still follow the general criteria I outlined much earlier, double-LPs gain some leniency in some quarters but generate some extra rules in return. The first, which we'll call the "sprawl" double-LP:

1. The "sprawl" double-LP must cover enough ground. If it doesn't, it's what we'll call the "under-sprawl" double-LP. If you do not have enough variation to cover two LPs, then don't do it. It may be bearable to go through the same shtick for one LP, but two is overkill. Simply put, you have enough room to tinker around, so do it! Don't waste the space on the same genre the whole time!

2. That being said, there is such thing as "over-sprawl," where you just cover way too much ground without stylistic focus and a core to what you're going for. This is typically the worst version of the double-LP, too much of everything, not enough of something. The "over-sprawl" double LP uses the extra space as room for experimenting. Do that in the studio! Don't release that if it's only use was to mess with that random studio effect! You're hurting the album in all quarters by going with the "over-sprawl" approach!

3. All Criteria established in my Mission Statement still apply, no questions asked. However, given the nature of a double-LP, flow can oftentimes be broken up LP by LP, or side by side, depending on the record. That rule requires the "double-LP exception," which I actually hinted at there.

The concept double-LP has a different set of criteria:

1. Does the concept deserve to be on two LPs? Is it really that expansive to require that second LP? Do you really need an extra 40 minutes to expound on your hero's walk from his garden to the grocery store? Probably not. But do you need an extra 40 minutes to talk about key events, themes, and motifs? If yes, then you need the second LP! Yes, this can apply to instrumental segues on a double-LP, which oftentimes are very capable of providing respite or a connecting piece to another section of a record.

2. Are all tracks thematically relevant? Related to the above rule but sort of distinct. It can musically fulfill the concept, or lyrically fulfill the concept, but if it doesn't, throw it out! It doesn't belong at all! This is basically a corollary to the "over-sprawl" rule with a specific application to double-LPs.

3. Same as the "sprawl" double-LP rule. Everything still applies. But with a concept double-LP, there simply is less room for flow problems, and flow separation (or lack thereof) becomes a much bigger issue.

Given the criteria, it's simply quite easier to craft a good "sprawl" double-LP than it is to craft a good "concept" double-LP. Here's a list of masterful double-LPs, and it's actually quite short (no order):

The Beatles - The Beatles

The Rolling Stones - Exile On Main St.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Electric Ladyland

The Clash - London Calling

Led Zeppelin - Physical Graffiti

Bob Dylan - Blonde On Blonde

Bob Dylan and the Band - The Basement Tapes

Miles Davis - Bitches Brew

The Who - Tommy

Derek and the Dominos - Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs

Bruce Springsteen - The River

Sonic Youth - Daydream Nation

The Minutemen - Double Nickels on the Dime

It's by no means the definitive list, but it's a good compilation of the good stuff when it comes to double-LPs. Each record I listed I would probably consider a must-listen at some point. Yes, it's going to be a full 70-90 minutes of your life to work through it, but I'll be damned if it won't be a 70-90 minutes very, very well spent. While it's definitely hard to apply my criteria to the Miles Davis record, really...who doesn't love that record (except the traditional jazz cats)?

I did want to mention what I consider to be the outer frontier of the double-LP: the triple-LP. Until this week, I was only able to think of two musicians who had even dared to compile a triple-LP: George Harrison and the Clash. And, coincidentally, they're both ridiculously good records...

George Harrison - All Things Must Pass

The Clash - Sandinista!

The only person since then that had even dared to venture into that territory just joined the field this week - Joanna Newsom - with the record Have One On Me. Maybe it should have been called Have Two On Me, because there's two extra LPs (and in this instance, yes, in the LP sense because the album spans over three LPs...meaning it is two hours long). Time will only tell if Joanna Newsom joins the ranks of the Clash and George Harrison as the only people to ever successfully produce a triple LP. Even daring to do it deserves many accolades...at least in my opinion.

Thursday, February 4, 2010

Punk Primer

It seems rather useless to write about punk, to be honest. Punk is about the gut feeling. Punk is about harnessing feelings. So what is the use of writing about punk? You put on punk, you get lost in the masses. But, as usual, the scholarly side of me (though there is not much that is scholarly about rock music) wants to break it down and present my theories and concepts with regards to punk music. So here goes...the nature of punk music says that what I'll be saying is useless and that you should ignore it (see: the "Ignore Alien Orders" sticker emblazoned on Joe Strummer's guitar), so do what you will:

Punk music essentially started with, well, proto-punk. Quite obvious, really. But where does proto-punk begin? I would argue that it began with the Velvet Underground. "I'm Waiting for the Man" and "White Light/White Heat" (to just name a few) move forward almost recklessly, propelled forward by some supernatural force. Trademark punk sound (which, as I will argue, hardly defines punk) is not there, but certainly the aesthetic was bred (reckless abandon) by the Velvet Underground (the White Light/White Heat record in its entirety is a pretty damn good lesson in proto-punk, but it's not for the faint of heart).

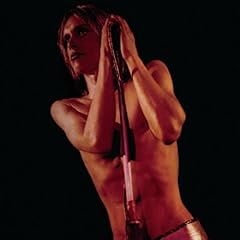

But, when most people envision proto-punk, it's not the Velvet Underground. It's the Stooges. These guys, for the unfamiliar (shame on you if you are unfamiliar):

That's the cover of what's arguably the most influential record in the development of punk music. It's strikingly simple (a classic hallmark of "punk" but not necessarily true), it's angry, it's mad, but it exhibits what I think is the classic "feeling" associated with punk music: alienation. The guitars bite, the guitars snarl, the bass is sinister, the drums insane, and everything just sounds like it's barreling forward only to self-destruct (another classic hallmark). Raw Power is simply one of the finest records around. I'm not sure where I would rank it, but it's really damn good. Ironically, everyone involved with Raw Power says that no mix of it is good (there are "Bowie Mix" haters, "Iggy Mix" haters, "Rough Mix" haters, and all). But that's not the point, because irrespective of the mix, this record shows proto-punk at its finest (and it actually outclasses many, many, punk records).

But onward to punk. The aforementioned feeling of alienation drives punk. Disillusionment with the establishment, the loss of connectedness to the world around, those are the feelings that drive punk. Alienation typically leads to either apathy or the outright rejection and revolt towards the offenders, and those choices are a very good approximation of the punk dichotomy. Naturally, I would hesitate to offer strict dichotomies when it comes to punk music, because artists can easily dip back and for, to and fro from one side of the dichotomy together, but it presents a stark view of the way punk music was an outlet for frustrations towards the alienation they faced. To put it in a more or less succinct manner, if you were punk, you were either a nihilist or an activist.

Nihilism is generally regarded as the not caring about anything. This camp is the apathetic camp, who have chosen to not care about their situation: they are essentially to disillusioned to even care about much at all and would much rather self-destruct than deal with it. I would argue that the Sex Pistols embodied this nihilistic side the best. The easy thing to do is point to the implosion of Sid Vicious, but I'm going to instead point to the track "No Feelings" off of, well, their only record. "I got no emotions for anybody else, you better understand...I'm in love with myself" is an example of pure nihilism.

The activists in the punk movement are your politi-punk bands, who choose to care and try to change their situation, and if they can't peacefully, well, force isn't out of the question. The Clash are the prime example of this. "White Riot" speaks, well, of itself, calling for drastic action because they have been sidelined and ignored (not in terms of race, mind you, but it's a class struggle). It's inherently possible to say that these groups were a bit Marxist, but when you're the lower class, a lot of things become an issue of class conflict.

But punk, after the feeling of alienation, is an aesthetic or mindset more than anything else. It's not "three chords and a sneer," which is apparently how most people define punk. Punk knows no limits. How else can you examine the fact that London Calling is so much more than just a punk record? It mashes anything and everything together to create a supernatural experience, but you still always know that they're all about the issues, but they just take care of it more than anyone else. Perhaps the blame can be put on punk itself. Punk prided itself on its simplicity, and so it became associated with less when it wanted to say more.

Joe Strummer, as I recall, said that punk is what you want it be, what you make it out to be, and you better damn well believe him. Even with the Mescaleros, his later output, such as Global A Go Go, I still saw that as a punk record. Just punk with an ear towards world music. You look at punk groups who have also seen "righteous" success (I'll deal with my usage of the term "righteous" here in a bit) and you see the Minutemen, whose Double Nickels on the Dime record stretches punk's sound to crazy limits while still definitively carrying the punk spirit.

And I come to my use of the term "righteous." There was a neo-punk movement in the 1990s powered by the likes of Green Day and blink-182 and the ilk. Let me just say that none of it is very good. They mostly capitalized on the "three chords and a sneer" and tried to run with it. And those groups got popular by abusing the spirit of punk. Dookie was probably the best of the crop, but in terms of where it belongs, it still doesn't rank very highly (it's a rather nihilistic record, and in that area, you can't come within a universe's length of the Sex Pistols there). Still, it's damning to see the way punk has been despoiled and stained. There are a few groups carrying the spirit of punk, but I'm not sure that I could call them completely punk bands.

I'm not sure we will ever see another truly punk band out there. I think our last chance left with this guy:

He was the last great punksman (if such a term could ever exist), the last shining light of hope where all was dark. Rest in peace, Joe Strummer (1952.08.21-2002.12.22). Every time I think about punk, I think about this angelic figure. The unlikely revival of punk kills me, because "righteous" punk music was the first thing I'd ever gotten into.

Labels:

Punk,

the Clash,

the Sex Pistols,

the Stooges,

The Velvet Underground

Thursday, January 21, 2010

Chameleons in Music

Ah, the chameleons in the world of rock music. Chameleons in the best sense preempt environment changes. If the winds of music are going one way, the chameleon was, in all likelihood, there first. But they ceaselessly reinvent themselves to the point where to try to describe the artist in one word, or even a sentence (or a paragraph, or so on and so forth...) is a fruitless exercise. There are only a couple of chameleons in rock music that are of note, and I think it's necessary to at least examine each chameleon in some sort of detail or length. These two are Bob Dylan and David Bowie, and they both have led stellar careers where each milestone coincides with some sort of reinvention and/or landmark work that either pioneered a genre or proved to be that genre's finest work.

But really, which image would best describe "Bob Dylan" as the man? You'd be hard-pressed to pick one picture and say "That there is everything Bob Dylan was."

He was a folk revivalist, a neo-folkie who brought the genre back into the popular consciousness pushed its boundaries in form. He then forsook folk for more fertile territories by going electric, infusing the ferocity of rock with a lyrical inventiveness that has never been replicated since. But then he became "the lonesome hobo" and then a country crooner. And then, in the wake of his marriage, became the epitome of lovesick and in one fell swoop created the "confessional singer-songwriter" genre, all while penning a classic album that simply is the best breakup album of all time, if not standing tall as one of the greatest records, ever. Next he found himself and became born again. That didn't last, though, as he changed his colors and became the world-weary, grizzled old wise man that he is today.

In every sense, he either invented the genre (neo-folk), or proved to produce the finest records in whatever genre he happened to be in at the time (Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde On Blonde, among the rest of them). Perhaps you could make an argument that in strict terms of music, you'd be hard-pressed to find a genre that Bobby D actually invented for himself. But I think that there's almost no such thing as a completely "new" genre: it's built from the blocks of older genres and appropriated and given a fresh new light, which is what Bob Dylan did.

Regardless, just by looking through the previous paragraph that condenses a 40 or so year career into a paragraph probably does Bob Dylan oodles of grave injustices. No man has ever been as slippery as Bob Dylan. Hard to get a hold of, because he is, and hard to get a hold of because he has changed too many times to account, to keep up with the times as they changed around him.\

Now, I could have also picked from a ton of possible photos for David Bowie, but of all the ones I could choose, I prefer this photo, as I wanted to avoid using the album cover for Low at every turn (because really, I would have no problem with that). But David Bowie has led almost as long as a career as Bob Dylan, with almost as many twists and turns, which were arguably more drastic than Dylan's.

First plumbing psychadelic folk, Bowie later turned to glam rock, which later became a brief foray into soul and R&B before he went entirely experimental and avant-garde with the so-called "Berlin Trilogy," a classic landmark. After "retreating" a bit into more accessible music for a long while, Bowie turned to electronica before basically spending his time reinventing his legacy.

While at first it doesn't seem like as many twists and turns as Dylan's career was, Bowie's were undoubtedly more revolutionary. Bowie essentially invented glam rock with Hunky Dory and the Ziggy Stardust record. He also pioneered the use of electronics in music and essentially helped form post-punk and New Wave with his "Berlin Trilogy." Those achievements alone are astounding, but when taken in the context that it was all basically done by one man, who had either the wits or just the fleeting sense of creativity to change his musical appearance so drastically, then this proposition becomes mind-blowing. Most artists spend their lives daydreaming about inventing genres and becoming a pervasive influence in music; David Bowie spent most of his time, well, inventing genres and becoming a pervasive influence in music.

-----------

And so, there you have it. They're a little brief, but I hope you get the gist of it. Dylan and Bowie were both quintessential chameleons: they never remained in a state of stasis for very long in their careers, as either they just kept on changing to their environment or actually creating a new environment around them. Because of their successes in their changes, they both have had lasting influences in rock music and have both created, together, at least 50 records that must be heard before a person dies. That's pretty damn impressive, right?

But really, which image would best describe "Bob Dylan" as the man? You'd be hard-pressed to pick one picture and say "That there is everything Bob Dylan was."

He was a folk revivalist, a neo-folkie who brought the genre back into the popular consciousness pushed its boundaries in form. He then forsook folk for more fertile territories by going electric, infusing the ferocity of rock with a lyrical inventiveness that has never been replicated since. But then he became "the lonesome hobo" and then a country crooner. And then, in the wake of his marriage, became the epitome of lovesick and in one fell swoop created the "confessional singer-songwriter" genre, all while penning a classic album that simply is the best breakup album of all time, if not standing tall as one of the greatest records, ever. Next he found himself and became born again. That didn't last, though, as he changed his colors and became the world-weary, grizzled old wise man that he is today.

In every sense, he either invented the genre (neo-folk), or proved to produce the finest records in whatever genre he happened to be in at the time (Highway 61 Revisited, Blonde On Blonde, among the rest of them). Perhaps you could make an argument that in strict terms of music, you'd be hard-pressed to find a genre that Bobby D actually invented for himself. But I think that there's almost no such thing as a completely "new" genre: it's built from the blocks of older genres and appropriated and given a fresh new light, which is what Bob Dylan did.

Regardless, just by looking through the previous paragraph that condenses a 40 or so year career into a paragraph probably does Bob Dylan oodles of grave injustices. No man has ever been as slippery as Bob Dylan. Hard to get a hold of, because he is, and hard to get a hold of because he has changed too many times to account, to keep up with the times as they changed around him.\

Now, I could have also picked from a ton of possible photos for David Bowie, but of all the ones I could choose, I prefer this photo, as I wanted to avoid using the album cover for Low at every turn (because really, I would have no problem with that). But David Bowie has led almost as long as a career as Bob Dylan, with almost as many twists and turns, which were arguably more drastic than Dylan's.

First plumbing psychadelic folk, Bowie later turned to glam rock, which later became a brief foray into soul and R&B before he went entirely experimental and avant-garde with the so-called "Berlin Trilogy," a classic landmark. After "retreating" a bit into more accessible music for a long while, Bowie turned to electronica before basically spending his time reinventing his legacy.

While at first it doesn't seem like as many twists and turns as Dylan's career was, Bowie's were undoubtedly more revolutionary. Bowie essentially invented glam rock with Hunky Dory and the Ziggy Stardust record. He also pioneered the use of electronics in music and essentially helped form post-punk and New Wave with his "Berlin Trilogy." Those achievements alone are astounding, but when taken in the context that it was all basically done by one man, who had either the wits or just the fleeting sense of creativity to change his musical appearance so drastically, then this proposition becomes mind-blowing. Most artists spend their lives daydreaming about inventing genres and becoming a pervasive influence in music; David Bowie spent most of his time, well, inventing genres and becoming a pervasive influence in music.

-----------

And so, there you have it. They're a little brief, but I hope you get the gist of it. Dylan and Bowie were both quintessential chameleons: they never remained in a state of stasis for very long in their careers, as either they just kept on changing to their environment or actually creating a new environment around them. Because of their successes in their changes, they both have had lasting influences in rock music and have both created, together, at least 50 records that must be heard before a person dies. That's pretty damn impressive, right?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)