Every artist has thought about making a double album. Few have done it, and even fewer have even met any sort of success doing it. Why has the double album been so appealing, and what determines the success (or failure) of a double album?

I think that the reason why the double LP has been so popular is that it gives artists a great amount of artistic lenience with what they want to pursue. If they don't have a particular direction in mind, they can make a double album going every sort of direction! It's actually a pretty convenient solution. This sort of smorgasbord approach is likely the most common approach when it comes to double albums: there's too much to cut out to make a single LP, either due to egos (i.e. the Beatles, perhaps) or because maybe there's just too much good material there (also i.e. the Beatles). Basically, the problem (too much stuff) is resolved by keeping the problem (too much stuff? keep it)...like throwing everything and the kitchen sink at a problem. Sometimes, the extra space is needed to expound on an album concept (closely intertwining with the art of the concept album), like the Who's Tommy. This last iteration is much less common, but its validity cannot be dismissed.

It's necessary to break the double-LP into two categories because each has to be graded on very different forms. While all albums should still follow the general criteria I outlined much earlier, double-LPs gain some leniency in some quarters but generate some extra rules in return. The first, which we'll call the "sprawl" double-LP:

1. The "sprawl" double-LP must cover enough ground. If it doesn't, it's what we'll call the "under-sprawl" double-LP. If you do not have enough variation to cover two LPs, then don't do it. It may be bearable to go through the same shtick for one LP, but two is overkill. Simply put, you have enough room to tinker around, so do it! Don't waste the space on the same genre the whole time!

2. That being said, there is such thing as "over-sprawl," where you just cover way too much ground without stylistic focus and a core to what you're going for. This is typically the worst version of the double-LP, too much of everything, not enough of something. The "over-sprawl" double LP uses the extra space as room for experimenting. Do that in the studio! Don't release that if it's only use was to mess with that random studio effect! You're hurting the album in all quarters by going with the "over-sprawl" approach!

3. All Criteria established in my Mission Statement still apply, no questions asked. However, given the nature of a double-LP, flow can oftentimes be broken up LP by LP, or side by side, depending on the record. That rule requires the "double-LP exception," which I actually hinted at there.

The concept double-LP has a different set of criteria:

1. Does the concept deserve to be on two LPs? Is it really that expansive to require that second LP? Do you really need an extra 40 minutes to expound on your hero's walk from his garden to the grocery store? Probably not. But do you need an extra 40 minutes to talk about key events, themes, and motifs? If yes, then you need the second LP! Yes, this can apply to instrumental segues on a double-LP, which oftentimes are very capable of providing respite or a connecting piece to another section of a record.

2. Are all tracks thematically relevant? Related to the above rule but sort of distinct. It can musically fulfill the concept, or lyrically fulfill the concept, but if it doesn't, throw it out! It doesn't belong at all! This is basically a corollary to the "over-sprawl" rule with a specific application to double-LPs.

3. Same as the "sprawl" double-LP rule. Everything still applies. But with a concept double-LP, there simply is less room for flow problems, and flow separation (or lack thereof) becomes a much bigger issue.

Given the criteria, it's simply quite easier to craft a good "sprawl" double-LP than it is to craft a good "concept" double-LP. Here's a list of masterful double-LPs, and it's actually quite short (no order):

The Beatles - The Beatles

The Rolling Stones - Exile On Main St.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Electric Ladyland

The Clash - London Calling

Led Zeppelin - Physical Graffiti

Bob Dylan - Blonde On Blonde

Bob Dylan and the Band - The Basement Tapes

Miles Davis - Bitches Brew

The Who - Tommy

Derek and the Dominos - Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs

Bruce Springsteen - The River

Sonic Youth - Daydream Nation

The Minutemen - Double Nickels on the Dime

It's by no means the definitive list, but it's a good compilation of the good stuff when it comes to double-LPs. Each record I listed I would probably consider a must-listen at some point. Yes, it's going to be a full 70-90 minutes of your life to work through it, but I'll be damned if it won't be a 70-90 minutes very, very well spent. While it's definitely hard to apply my criteria to the Miles Davis record, really...who doesn't love that record (except the traditional jazz cats)?

I did want to mention what I consider to be the outer frontier of the double-LP: the triple-LP. Until this week, I was only able to think of two musicians who had even dared to compile a triple-LP: George Harrison and the Clash. And, coincidentally, they're both ridiculously good records...

George Harrison - All Things Must Pass

The Clash - Sandinista!

The only person since then that had even dared to venture into that territory just joined the field this week - Joanna Newsom - with the record Have One On Me. Maybe it should have been called Have Two On Me, because there's two extra LPs (and in this instance, yes, in the LP sense because the album spans over three LPs...meaning it is two hours long). Time will only tell if Joanna Newsom joins the ranks of the Clash and George Harrison as the only people to ever successfully produce a triple LP. Even daring to do it deserves many accolades...at least in my opinion.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Thursday, February 4, 2010

Punk Primer

It seems rather useless to write about punk, to be honest. Punk is about the gut feeling. Punk is about harnessing feelings. So what is the use of writing about punk? You put on punk, you get lost in the masses. But, as usual, the scholarly side of me (though there is not much that is scholarly about rock music) wants to break it down and present my theories and concepts with regards to punk music. So here goes...the nature of punk music says that what I'll be saying is useless and that you should ignore it (see: the "Ignore Alien Orders" sticker emblazoned on Joe Strummer's guitar), so do what you will:

Punk music essentially started with, well, proto-punk. Quite obvious, really. But where does proto-punk begin? I would argue that it began with the Velvet Underground. "I'm Waiting for the Man" and "White Light/White Heat" (to just name a few) move forward almost recklessly, propelled forward by some supernatural force. Trademark punk sound (which, as I will argue, hardly defines punk) is not there, but certainly the aesthetic was bred (reckless abandon) by the Velvet Underground (the White Light/White Heat record in its entirety is a pretty damn good lesson in proto-punk, but it's not for the faint of heart).

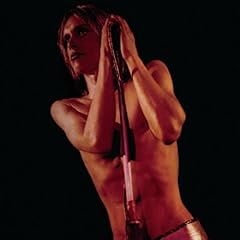

But, when most people envision proto-punk, it's not the Velvet Underground. It's the Stooges. These guys, for the unfamiliar (shame on you if you are unfamiliar):

That's the cover of what's arguably the most influential record in the development of punk music. It's strikingly simple (a classic hallmark of "punk" but not necessarily true), it's angry, it's mad, but it exhibits what I think is the classic "feeling" associated with punk music: alienation. The guitars bite, the guitars snarl, the bass is sinister, the drums insane, and everything just sounds like it's barreling forward only to self-destruct (another classic hallmark). Raw Power is simply one of the finest records around. I'm not sure where I would rank it, but it's really damn good. Ironically, everyone involved with Raw Power says that no mix of it is good (there are "Bowie Mix" haters, "Iggy Mix" haters, "Rough Mix" haters, and all). But that's not the point, because irrespective of the mix, this record shows proto-punk at its finest (and it actually outclasses many, many, punk records).

But onward to punk. The aforementioned feeling of alienation drives punk. Disillusionment with the establishment, the loss of connectedness to the world around, those are the feelings that drive punk. Alienation typically leads to either apathy or the outright rejection and revolt towards the offenders, and those choices are a very good approximation of the punk dichotomy. Naturally, I would hesitate to offer strict dichotomies when it comes to punk music, because artists can easily dip back and for, to and fro from one side of the dichotomy together, but it presents a stark view of the way punk music was an outlet for frustrations towards the alienation they faced. To put it in a more or less succinct manner, if you were punk, you were either a nihilist or an activist.

Nihilism is generally regarded as the not caring about anything. This camp is the apathetic camp, who have chosen to not care about their situation: they are essentially to disillusioned to even care about much at all and would much rather self-destruct than deal with it. I would argue that the Sex Pistols embodied this nihilistic side the best. The easy thing to do is point to the implosion of Sid Vicious, but I'm going to instead point to the track "No Feelings" off of, well, their only record. "I got no emotions for anybody else, you better understand...I'm in love with myself" is an example of pure nihilism.

The activists in the punk movement are your politi-punk bands, who choose to care and try to change their situation, and if they can't peacefully, well, force isn't out of the question. The Clash are the prime example of this. "White Riot" speaks, well, of itself, calling for drastic action because they have been sidelined and ignored (not in terms of race, mind you, but it's a class struggle). It's inherently possible to say that these groups were a bit Marxist, but when you're the lower class, a lot of things become an issue of class conflict.

But punk, after the feeling of alienation, is an aesthetic or mindset more than anything else. It's not "three chords and a sneer," which is apparently how most people define punk. Punk knows no limits. How else can you examine the fact that London Calling is so much more than just a punk record? It mashes anything and everything together to create a supernatural experience, but you still always know that they're all about the issues, but they just take care of it more than anyone else. Perhaps the blame can be put on punk itself. Punk prided itself on its simplicity, and so it became associated with less when it wanted to say more.

Joe Strummer, as I recall, said that punk is what you want it be, what you make it out to be, and you better damn well believe him. Even with the Mescaleros, his later output, such as Global A Go Go, I still saw that as a punk record. Just punk with an ear towards world music. You look at punk groups who have also seen "righteous" success (I'll deal with my usage of the term "righteous" here in a bit) and you see the Minutemen, whose Double Nickels on the Dime record stretches punk's sound to crazy limits while still definitively carrying the punk spirit.

And I come to my use of the term "righteous." There was a neo-punk movement in the 1990s powered by the likes of Green Day and blink-182 and the ilk. Let me just say that none of it is very good. They mostly capitalized on the "three chords and a sneer" and tried to run with it. And those groups got popular by abusing the spirit of punk. Dookie was probably the best of the crop, but in terms of where it belongs, it still doesn't rank very highly (it's a rather nihilistic record, and in that area, you can't come within a universe's length of the Sex Pistols there). Still, it's damning to see the way punk has been despoiled and stained. There are a few groups carrying the spirit of punk, but I'm not sure that I could call them completely punk bands.

I'm not sure we will ever see another truly punk band out there. I think our last chance left with this guy:

He was the last great punksman (if such a term could ever exist), the last shining light of hope where all was dark. Rest in peace, Joe Strummer (1952.08.21-2002.12.22). Every time I think about punk, I think about this angelic figure. The unlikely revival of punk kills me, because "righteous" punk music was the first thing I'd ever gotten into.

Labels:

Punk,

the Clash,

the Sex Pistols,

the Stooges,

The Velvet Underground

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)