There are certain figures regarded as immortal in rock music. To name a few:

Jimi Hendrix

Jim Morrison

John Lennon

Bob Marley

Ray Charles

Marvin Gaye

George Harrison

Kurt Cobain

Joe Strummer

Johnny Cash

Stevie Ray Vaughn

John Bonham

Elliot Smith

Keith Moon

and the like. I don't necessarily agree with some inclusions (I'm not sold on Morrison and Cobain, for starters), but for all intents and purposes those are commonly known "immortals" in rock music. What holds these together? They're all dead. And this leads me to my first Immutable Law in Rock Music:

"

To be truly immortal in Rock Music, one must die.

"

Of course, this makes zero sense at first. If you're dead, how are you alive? You're no longer making music. But take a look. Posthumous careers for many of these careers have either overshadowed or recharged some careers. I'm going to pull a different example than some of the people I listed above to prove my point: Ian Curtis of Joy Division.

Joy Division were not really well known when Curtis died. They were on the rise, but not really at that point yet where they got it "good." And then, poof! Ian Curtis, gone from the world. And then everyone discovered "Love Will Tear Us Apart," and the landmark records Unknown Pleasures and Closer. Then, all of a sudden, Joy Division were kind of a big deal. This allowed New Order (the rest of Joy Division) to get a head start, and has furthermore led to reissues, reprintings, and box sets of Joy Division's work. If Ian Curtis had died, would Joy Division have been big? Sure. Would they have been as big as they are now had Ian Curtis died? Arguably, no. Ian Curtis' death casts a long shadow over the melancholia that permeates every Joy Division song. In light of his depression and epilepsy, Joy Division records and songs gain a whole backstory and a whole new meaning. Divorced from their meaning, the songs are quite obviously powerful, muscular, and constantly effecting, but with this meaning every Joy Division song becomes a tour de force that simply obliterates the listener when heard.

The context of death makes everything about the artist more striking, granting the band/artist an aura that is impossible to penetrate. To elaborate on the above example, Ian Curtis, on his dying day, watched a Herzog film, put on Iggy Pop's the Idiot, and then hung himself. Curtis has attained a sort of mysticism due to that. Marvin Gaye was shot by his father, John Lennon was assassinated, while Kurt Cobain and Jimi Hendrix died due to overdoses. They're all now seen with a sort of reverence, an air of the mystic thanks to their deaths.

Each person who has died in the midst of their career has, in a sense, gained a sort of "impenetrable fog" that protects them from any sort of heated criticism and guarantees them a favorable standing in the world of rock music. I'm not saying it's undeserved. Lennon obviously deserves the "impenetrable fog"; his work with the Beatles, Plastic Ono Band and Imagine are all stone-cold classics and monoliths in rock music, and as an activist his edge has been unmatched. But Walls and Bridges? Some Time In New York City? Neither record is much better than mediocre, in my humble opinion. But his death erased any sort of criticism that could be levied against him.

This is why I'm inclined to believe Paul McCartney often suffers in critic circles: he's still around, he's still pounding it out, but either because he's been oft considered as the "soft" Beatle or because of his long career which has led to a fair number of duds to go alongside his many, many studs, he's likely the least respected Beatle (though perhaps Ringo also is given this same title). Now of course, saying someone is the least-respected Beatle is saying the fourth-most respected artist of all time, but that's neither here nor there. John Lennon has two (to three, depending on your level of scathing) duds to go alongside his studs. Granted, it's folly to extrapolate a career and look at sample sizes to examine careers of rock musicians, but it should be duly noted.

I'm also not ragging against John Lennon. Let me make that clear. John Lennon is the fucking man. I observe his birthday and his dying day every year. I don't take the day off, but for that whole day, John Lennon, everything he did and everything he stood for is always on my mind. But his death has granted him a place in the hallowed hall of rock immortals, perhaps given a slightly easier screening process than others. As have countless others, for better or for worse.

If you look at the ripples caused by a musician's death, the effect is pretty obvious. At least nowadays, the artist in question is rewarded with many, many posthumous awards and accolades. George Harrison was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame shortly after his death. Ray Charles won a whopping eight Grammies from his record, Genius Loves Company, which was released two months after his death. Johnny Cash's American IV won a few CMA's and his rendition of "Hurt" absolutely slayed everyone and reaped some rewards soon after he passed (myself included...but his rendition of "Hurt" is great regardless of the circumstances).

The general rule? In rock music, sometimes it's better to die than to live. It doesn't make any sense, really, but it's true. It's truly a peculiar phenomenon. But it's observable. To refuse to acknowledge its existence is shortsighted. It's not talked about a lot...but it's there. Sort of like a dirty little secret. It's also something that should never be wished on someone. Death for the profit of afterlife. Perhaps it is the manifestation of "what could have been?" had they continued to be around; continued to be the great musicians they were.

Key, though, is to enjoy the careers that these immortals have brought us before their dying breath. In this sense, each album is worth more because there are less albums around. So it's therefore to critical to enjoy each landmark work each immortal brings us, to listen and bask in its eternal glory.

Monday, December 21, 2009

Sunday, December 20, 2009

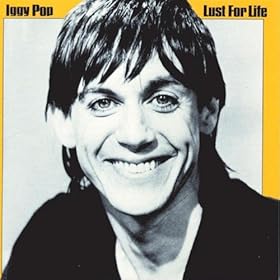

Record of the Moment: Iggy Pop - Lust for Life

Somehow, it is hard to imagine that the cheeky young fellow who appears on this record cover to be the same gaunt-faced man who gave the death stare on the cover of Raw Power. It doesn't seem to add up. Here, the dude is happy. Look at that smile. The man on the cover of Raw Power looks like he wants to tear your throat out and eat it in front of your children. And just look at the title of each record: Lust for Life against Raw Power. One implies positivity, the other implies negativity.

But that's where Iggy Pop ended up. After the royal collapse of the Stooges, and a stint in the hospital, Iggy Pop was back in business. He'd cleaned up, essentially (though this probably isn't totally true). But the glaring difference between the cover of the last Stooges and the cover for this record sort of perpetuates that myth. And in some sense, the music is a little lighter. By no means does this mean Iggy Pop went "lite" on the populace. Nope. I don't think Iggy Pop would be caught dead going "lite," because that is simply the way Iggy Pop is.

Compared to the Idiot, the previous release, Lust for Life is a return to form for Iggy Pop. Personally, in my historical pursuits as a rock scholar, I consider the Idiot to be a sort of half-Bowie, half-Pop record. It's obviously still Iggy. But the music is obviously a predecessor to Bowie's groundbreaker, Low. Therefore, the Idiot is sort of the lost brother to Bowie's trilogy (I'd argue that the Idiot should be included in the "trilogy"; thus expanding the concept into a "quadrilogy"). Some people disown the Idiot for its Bowie-ness. I refuse to do so, personally. Regardless, Lust for Life showed that Pop still not only had his own lyrical edge, but his edge as a musician.

The drums that kick off the record instantly blow open your mind. It's big, it's huge, and instantly memorable (and apparently easily sullied and stained: I'm looking at you, Jet). And then it kicks into gear. The younger and angrier Iggy Pop is largely missing; here instead is an older, wiser Iggy Pop, who knows better now that he's escaped his vices. But of course, he still acknowledges their existence (see: "Some Weird Sin"), because who couldn't? Your vices haunt you forever. Iggy captures it perfectly; after all, of all the people who are familiar with self-destruction, Iggy Pop pretty much tops the list.

But this Iggy Pop is largely over that hill and out of that Hell, and he knows it. The way "Success" gleefully careens along, almost teetering on the edge of collapse but always steady...it's infectious. "The Passenger" is similarly enchanting, but not because it's necessarily a "happy" track; it's an Iggy Pop seemingly at peace. The barroom rock of "Turn Blue" is indicative of Iggy's still-present edge, both morbid and scathing in its attacks, but almost sarcastic in its musings. The track is a reference to Iggy Pop's previous struggles with drugs, as easily discerned, but for all anyone knows the implications are much wider.

While the music itself is nowhere near as ear-bleed-inducing as Raw Power is (which was intentional), that is not to say that Lust for Life is toothless. Tracks such as "Neighborhood Threat" prowl along menacingly, with Iggy Pop's voice of "doom," so to speak, going from its tremble-causing baritone to shattering screams and yelps in a heartbeat...all constantly affecting, if sometimes slightly grating (or very grating, depending on your disposition towards the singing abilities of Iggy Pop). The funk-tinged (most Bowie-like) romp, "Fall in Love with Me" stomps along in a marvelous fashion, with Iggy half-crooning the title line over a contagious groove that is hard to deny.

I could speak at length about every track, but I will stop here. Needless to say, Lust for Life is essential. Standing alone, the record is perfect. Its influence is widespread. Lust for Life is a perfect example of proto-punk. Perhaps not as "punk" as what is typically evinced (see: Sex Pistols and early Clash) but indicative of the spirit of punk...ever-restless. Not necessarily experimental or groundbreaking, but essentially free-spirited at its core.

Saturday, December 12, 2009

The Man #4: Tom Waits

When I refer to "The Man," I refer to titans in my music world. Perhaps later they will warrant their own "The Man" entries (as you may have noticed, I am terribly ineffective when it comes to maintaining series outside of "Record of the Moment"), but there are three people who currently rank ahead of Mr. Waits:

1. Jeff Tweedy

2. Bob Dylan

3. Lou Reed

and one who ranks behind:

5. Joe Strummer

Given that this is my current list, it is subject to flux. However (and this is a potential next entry if I get around to it), Jeff Tweedy will always be my number one. See my second "Records of Great Influence" entry here for the tip of the iceberg regarding the debt I owe Mr. Jeff Tweedy. Or, if you prefer Stephen Colbert's name for the guy, Geoffrey Velvet. The rest are obvious. Dylan, Reed, and Strummer are immutable figures in rock music, gods among mortals like you and I. But Tom Waits is the oddball in this group.

And that's the way I'd describe Tom Waits to someone if they had never heard of him. He is a total oddball. But he's also far and away one of the best songwriters in the 20th century and beyond. But beyond that there's a necessary chasm between "early Waits" and "later Waits."

"Early Waits" is the barroom, lounge music Tom Waits. Pretty jazzy, a little simpler, heavily piano-based. "Later Waits" is probably the longer, more prolific period of Waits. Heavily based in old-school blues, delighting in peculiar instrumentation, peculiar percussion rhythms, it's basically the darker cousin of "early Waits." My description of later Tom Waits would go like this, since otherwise my description doesn't help:

"Imagine like walking into a real seedy bar in like the 20's or 30's and there's some bar band playing some strange burlesque, vaudevillian music. It sounds familiar, yet because of the way it's constructed, it sounds like the bastard child of Howlin' Wolf and the Devil."

The most obvious thing, though, is the voice. Early Tom Waits maintains a light barroom croon that sounds youthful and full. Later Tom Waits sounds world-weary, war-ravaged, dogged by the devil; ranging from a sort of sinister growl to a furious and explosive roar.

But that is not to say that "early Waits" is better than "later Waits" or vice versa. It's more of a "which Waits do I want to hear right now?" and it's there. Boom. Early Waits? I'll put on Closing Time, his superb debut. Later Waits? I'll put on his landmark Rain Dogs, his Grammy-winning Bone Machine, or even put on his mega-package Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers, & Bastards. Or if I'm looking for a sort of "here is all of Tom Waits" sort of deal, I'll put on his most recent live record, Glitter and Doom Live.

Why is he one of "the Men"? Partially because he is such an oddball. How has the guy maintained a career playing this sort of music? Not because it's bad, because I love it all to death (or why else would I be writing this?). But commercially, it at first seems totally, totally suicidal. Totally anti-commercial, letting his music exist without being sullied by the post-industrial landscape that so often stains music through commercialism. It's a perfect recipe for disaster, when you look at the landscape now. Still, like the vagrants, the homeless, and the drunks that Tom Waits often writes about, he persists in spite of the changing tides of music. The man does what he wants, and that's one of the other things I love about him. Not about to bend to the will of any man. He plays what he wants. And, well, if you mess with him, he'll probably sue you too (Waits has a long history of suing people for wronging him). Well, if I messed with Tom Waits I'd probably deserve to be sued, too.

That's why I love Tom Waits. That's why he's my Man #4. This favorite quote of mine sums up Tom Waits extremely well, via Tom Waits himself:

"My kids are starting to notice I'm a little different from the other dads. 'Why don't you have a straight job like everyone else?' they asked me the other day. I told them this story: In the forest, there was a crooked tree and a straight tree. Every day, the straight tree would say to the crooked tree, 'Look at me...I'm tall, and I'm straight, and I'm handsome. Look at you...you're all crooked and bent over. No one wants to look at you.' And they grew up in that forest together. And then one day the loggers came, and they saw the crooked tree and the straight tree, and they said, 'Just cut the straight trees and leave the rest.' So the loggers turned all the straight trees into lumber and toothpicks and paper. And the crooked tree is still there, growing stronger and stranger every day."

Saturday, November 28, 2009

Record of the Moment: R.E.M. - Automatic for the People

Recently I have gotten into R.E.M., and I'm honest in saying that I never really heard them (in the way of placing a song to a band) before I somehow got the urge to pick up some of their records. Listening to them, I realize that I'd somehow heard many of these songs before, though I had never really associated them with R.E.M. Of course, that's changed now. R.E.M. is excellent stuff. I could have picked any assortment of records here (Murmur, Reckoning, Document could have been chosen), but I went with Automatic for the People in this instance.

This record is probably comes out as my favorite R.E.M. record thus far. Perhaps it is because ths record is a little more mid-tempo, and little more "folksy" than the others, but I connect to this record more than the others. But it's also easy to argue that R.E.M. were on the top of their game with Automatic for the People. R.E.M. wanted to change their musical direction, away from what they had done on the previous record, but it didn't happen. Perhaps it was just the residual of what they were doing previously, but the fact of the matter is the batch of songs on this record could not be expressed in any other way. Tracks like "Sweetness Follows" prowl along majestically in melancholy, while "Everybody Hurts" portrays a more personal, reserved melancholy.

Of course, the word repeated here is melancholy. This record is a lot slower, much more ruminative on "life" topics like love, life and death. Typically every songwriter's staple topics, but Stipe and co. execute much more effectively than your average dude. In some ways, this is a perfect alt-country record. No, R.E.M. were not an alt-country band, but this record shows those qualities and proves to be pretty damn catching and gripping. That is not to say that R.E.M. don't have a connection to the alt-country scene, as guitarist Peter Buck produced Uncle Tupelo's folk-revival masterpiece March 16-20, 1992. But this record sounds the part.

Drawing heavily from the folk tradition, most of the numbers are essentially ballads. "Nightswimming" and the like, you know. While this record has a copious amount of sadness and melancholy interwoven into it, those subject matters are never treated without dignity. And that is key. Too many groups "embrace the sadness" and become sappy affairs. At some point, take it too seriously and the whole thing becomes a massive caricature of itself. R.E.M. deftly avoid this problem, even as many of those ballads are accompanied by string sections written by John Paul Jones of Zep fame.

I can talk and talk about this song and that song and the way this part in the one song does this particular thing, but it's really the whole album experience that makes it. Something you just have to hear. And for that, R.E.M.'s Automatic for the People is my record of the moment.

Thursday, November 26, 2009

In Defense Of: The Velvet Underground - Loaded

You may be confused as to why I am choosing to defend this record. This is already a perfect record. I mean, it's the Velvet fucking Underground, right? But in this first entry for the In Defense Of: series, I choose to defend this record in comparison to the other Velvet Underground records.

You may be confused as to why I am choosing to defend this record. This is already a perfect record. I mean, it's the Velvet fucking Underground, right? But in this first entry for the In Defense Of: series, I choose to defend this record in comparison to the other Velvet Underground records.Because let's face it, every Velvet Underground record is a masterpiece. The Velvet Underground & Nico? Please, let's move on, because A. I've already discussed it at length previously and B. if you don't like the record, you are doomed for an existence in the Hellscape of rock and roll. White Light/White Heat is an experimentalist's dream come true, with all the avant-garde elements finally coming to fruition in a hectic and chaotic wall of noise surrounding the disarming beauty of "Here She Comes Now." The Velvet Underground is a much quieter affair, focusing much more on that same unguarded beauty in "Here She Comes Now," with just as good results. It's still a visceral record, but it's a quiet sort of visceral, one that silently pulls at your heart rather than just sort of tearing it out.

But Loaded? It's sort of the black sheep in the VU canon. Lou Reed's voice was deteriorating at a fairly alarming rate (Doug Yule had to often pick up Lou's leads on tour when his voice gave out). And for the recording of Loaded, Moe Tucker, the percussionist, was out on maternity leave, basically. So you see, the original Velvets were losing it. The drummer gone and the lead man perpetually listed as "Questionable" on every day of touring or recording (this is a pro football reference, for those who do not understand)? Not a great recipe for success.

And since the Velvets had finally secured the funds to make something even remotely polished, this subjected them to the thumb of the record label (whereas before they were allowed to really roam as free as they wished). Hence the title, Loaded, 'cause all the label wanted was a record loaded with hits...get it? It's probably a behind-the-back jibe at the label, knowing Lou Reed. But with those extra funds to achieve a bigger sound came the risk of having to sacrifice artistic freedom for commercial viability (the crux of the issue for any self-respecting artist).

Loaded proved a couple of things: the first is that Lou Reed could write anthemic, truly catchy pop songs. "Sweet Jane" is as anthemic as it gets. You just want to scream "Sweet Jane" along with Lou. "Who Loves the Sun"? I don't, thanks to Lou (and Doug for the vocal). And so on and so forth. The second thing is that (at least in those days) it was possible to perfect art without sacrificing it for commerical viability. "Sweet Jane" and "Rock & Roll" were fairly large hits (and still receive play today) while still being legitimate songs in their own right, and being able to form those tracks and the others into a legitimate album.

While Loaded is already a virtual masterpiece, the "What could have been?"s that plague the development of this record lead us to figure that, man, if most of it could have been, how much more awesome could this record even get? Numerous Velvets have sort of ragged on the record itself. Morrison wanted all the vocal leads to have been done by Lou. Doug Yule himself thinks he may have been a little overused on the record (he even stepped in on drums in Moe Tucker's absence).

I am of the opinion that all this "What could have been?" talk sort of diminishes the view that people have on the record. Let's focus our eyes on the prize. Evaluate what you have, not what you could have had. You're better off that way. And when you take that, what you have is a record of pure pop perfection. The other thing that always puts a downer on this record is the past record of the Velvets. Pioneers in art-rock, proto-punk (and therefore punk), experimental, and avant-garde, where does this fit in? It really doesn't. Loaded is simply a pop record. But when disassociated from the rest of the Velvets' legacy, well, it turns out to be a fantastic record. And that is why I chose to defend Loaded in this entry, though it shouldn't need defense. Loaded is regarded as inferior because of its associates. That is no way to treat a masterpiece.

Sunday, November 22, 2009

Double-Header: The Gumption Centers Mission Statement

I have not done too much substantive with regards to music this month, so I present to you a double-header today in a currently successful effort to put off whatever schoolwork I should be doing.

Now, my very very first post introduces everything, but a bit of thinking has led me to some interesting things:

1. I think it would be awesome if I eventually could teach a History of Rock and Roll class. Like at any University. Like, you know, MUS 252 at OSU. That would be cool.

2. I can already expect that I would do better than whatever scrub is teaching it right now.

3. But here's the rub, and where we get to my Mission Statement: with regards to "rock and roll" as we know it, the ALBUM is the highest form of music. There is nothing better. No A-side/B-side can ever conquer the sheer artistic perfection that an album can.

So here, let me restate that. The Mission Statement of Gumption Centers:

"

Rock and roll music is an esteemed form of popular music and, on the whole, music. In this genre, the masterwork comes in the form of the album. There is no greater joy to the ears than putting on the perfect LP, to be taken away to a different realm of existence for the duration of that LP. The LP, the record is the barometer with which all albums and any so-styled rock and roll artist should be measured. Any rock and roll artist who does not take the album seriously should therefore not be taken seriously.

"

The album is the greatest chance any artist has to make a real statement. While albums inherently haven't always been treated as total and coherent works (see: the Beatles' Please Please Me, With the Beatles, Beatles For Sale, Help!), it is still of paramount importance that the album projects a clear, coherent image of the group - how else do albums like the Beatles, Exile On Main St. hold up in all their splendor? The Beatles is a severely fractured record, with Lennon's searing confessionals, McCartney's dalliances with music hall styles, Harrison's increasingly successful forays into spirituality, and Ringo's general playfulness, so how can it hold up? Well, it's because the Beatles simply provided a coherent sound and existence as the group, no matter how far they were drifting at the time. It all sounded like the Beatles, and it all was good.

And so we come to this...what makes a good album? Heretofore, I list my criteria:

1. The album must be largely void of weak tracks. One exceedingly weak track severely hurts the album as an entire form. There is no forgiveness for a weak track, but there is always forgiveness if there is no "#1 World Single For The Next 50 Years" on the record.

2. The album must present a cohesive view of what the artist is trying to achieve.

3. The album must maintain proper flow. The artist should be mindful that in playing a record the entire way through that they do not want to put the listener to sleep with seven straight slow tracks nor pound the listener's head in with seven ear-bleeders (usually excepted in this instance: punk). But it is also of great importance that tracks flow into one another, with a minimal use of "reset buttons" to suddenly adjust the flow of a record (and excepted in this instance: switching sides on an LP or switching an LP).

Those are really the three criteria. It doesn't seem like a lot, but it actually is. And if it seems exceedingly harsh, I'd like to think that it is because that I take the album as an art form very seriously. Heretofore I will go through what I consider the top five records of all time and grade them based on my criteria (I am using my list from my very very first entry, which I still find correct):

1. Bob Dylan - Highway 61 Revisited

1. Bob Dylan - Highway 61 Revisited

Weak tracks? Absolutely not. From "Like A Rolling Stone" through "Desolation Row," Bob Dylan is at the tiptop of his game. Every track is utterly visceral and totally gripping, as Dylan weaves words, stories, myths and dreams around the listener about such fantastical characters as Cinderella and Casanova in "Desolation Row" to Sweet Melinda in "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues." And as a bonus, there is the "#1 World Single For The Next 50 Years" so coveted by everyone, and its name is "Like A Rolling Stone." Is the album cohesive, in that it presents a unified view of the artist? Yes. Dylan is at his most obtuse here, but that doesn't mean whatever hazy view lyrically is supported by some hazy combination of instrumentation. The backing band here is on fire, providing Dylan a perfect and consistent backdrop with which to paint on. Listening to this record, you realize that Dylan paints in a similar fashion with each song, which ensures cohesion in the record. Proper flow? Check. Every track seamlessly flows into one another, with the proper amount of pacing from the open to the close. Done. No need to explain any more. IF you think I do, you have head issues. Not to offend, but seriously. This record is perfect in every way.

2. The Beatles - Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

You really can't write anything original about this record because it's already been said. It's an immaculately crafted concept album, thus satisfying every criterion. Next.

3. The Band - Music From Big Pink

No, no weak tracks here. Super-hit (and therefore maligned for its pervasive appearance in popular culture) with "The Weight." "Chest Fever" grooves just as good as James Brown, while the ballads like "In A Station" and "Lonesome Suzie" are impeccably powered along by Richard Manuel's angelic singing. This record is cohesive in that it essentially is representing America and its rural and core values (see my previous entry on the Band, titled It Must Be the Beards: "America" and "Common Sense" in Rock Music). And it flows lazily from one track to another, never hurrying but never lulling the listener into stupor with impeccably timed more upbeat tracks, but since the Band's sound and vision is so united, the flow is never "off" ever during the record.

4. The Clash - London Calling

Weak tracks? No, you can't really say that there are any exceedingly weak tracks. While "Koka Kola" isn't exactly "Rudie Can't Fail" or "London Calling," it's certainly not chaff, because it's an essential pastiche that plays an integral role in the record. You also have the major hit factor with both "Train In Vain (Stand By Me)" and "London Calling," so there's that criterion checked off. A cohesive view? I would argue that. It seems stylistically all over the place. There's heavy reggae influences in "Guns of Brixton" to the roar of the blues rip-off "Brand New Cadillac" to the light bar jazz of "Jimmy Jazz" (I swear that wasn't intentional). But the cohesive view? Punk has no boundaries. Punk is an aesthetic unbounded by genre and style and sound. The claim is that punk is capable of everything. And I think they accomplished it. The flow is certainly there, with enough energy to instill fear into the hearts of the ignorant and enough "downtime" (though I wouldn't really call it such) to allow for recharging before taking up the crusade once again.

5. The Beach Boys - Pet Sounds

This is also one of those records that is almost impossible to write about now. Flawless, stunning, and perfect in every way, it is an encapsulation of the innocence of youth, growing up (but sincerely not really wanting to), and the fond reminiscence of those youthful days where all that mattered was "you" and "me."

So there you go. There are countless albums that can be considered pretty perfect, but these five stand tall, heads and shoulders above the rest. Always and forever. It is highly unlikely that any record from here on out will conjure up the same effects on listeners that those five records have had on the rock and roll soundscape. For better or for worse, those records cast a shadow on everything else that has ever been and will ever be released.

Now, my very very first post introduces everything, but a bit of thinking has led me to some interesting things:

1. I think it would be awesome if I eventually could teach a History of Rock and Roll class. Like at any University. Like, you know, MUS 252 at OSU. That would be cool.

2. I can already expect that I would do better than whatever scrub is teaching it right now.

3. But here's the rub, and where we get to my Mission Statement: with regards to "rock and roll" as we know it, the ALBUM is the highest form of music. There is nothing better. No A-side/B-side can ever conquer the sheer artistic perfection that an album can.

So here, let me restate that. The Mission Statement of Gumption Centers:

"

Rock and roll music is an esteemed form of popular music and, on the whole, music. In this genre, the masterwork comes in the form of the album. There is no greater joy to the ears than putting on the perfect LP, to be taken away to a different realm of existence for the duration of that LP. The LP, the record is the barometer with which all albums and any so-styled rock and roll artist should be measured. Any rock and roll artist who does not take the album seriously should therefore not be taken seriously.

"

The album is the greatest chance any artist has to make a real statement. While albums inherently haven't always been treated as total and coherent works (see: the Beatles' Please Please Me, With the Beatles, Beatles For Sale, Help!), it is still of paramount importance that the album projects a clear, coherent image of the group - how else do albums like the Beatles, Exile On Main St. hold up in all their splendor? The Beatles is a severely fractured record, with Lennon's searing confessionals, McCartney's dalliances with music hall styles, Harrison's increasingly successful forays into spirituality, and Ringo's general playfulness, so how can it hold up? Well, it's because the Beatles simply provided a coherent sound and existence as the group, no matter how far they were drifting at the time. It all sounded like the Beatles, and it all was good.

And so we come to this...what makes a good album? Heretofore, I list my criteria:

1. The album must be largely void of weak tracks. One exceedingly weak track severely hurts the album as an entire form. There is no forgiveness for a weak track, but there is always forgiveness if there is no "#1 World Single For The Next 50 Years" on the record.

2. The album must present a cohesive view of what the artist is trying to achieve.

3. The album must maintain proper flow. The artist should be mindful that in playing a record the entire way through that they do not want to put the listener to sleep with seven straight slow tracks nor pound the listener's head in with seven ear-bleeders (usually excepted in this instance: punk). But it is also of great importance that tracks flow into one another, with a minimal use of "reset buttons" to suddenly adjust the flow of a record (and excepted in this instance: switching sides on an LP or switching an LP).

Those are really the three criteria. It doesn't seem like a lot, but it actually is. And if it seems exceedingly harsh, I'd like to think that it is because that I take the album as an art form very seriously. Heretofore I will go through what I consider the top five records of all time and grade them based on my criteria (I am using my list from my very very first entry, which I still find correct):

1. Bob Dylan - Highway 61 Revisited

1. Bob Dylan - Highway 61 RevisitedWeak tracks? Absolutely not. From "Like A Rolling Stone" through "Desolation Row," Bob Dylan is at the tiptop of his game. Every track is utterly visceral and totally gripping, as Dylan weaves words, stories, myths and dreams around the listener about such fantastical characters as Cinderella and Casanova in "Desolation Row" to Sweet Melinda in "Just Like Tom Thumb's Blues." And as a bonus, there is the "#1 World Single For The Next 50 Years" so coveted by everyone, and its name is "Like A Rolling Stone." Is the album cohesive, in that it presents a unified view of the artist? Yes. Dylan is at his most obtuse here, but that doesn't mean whatever hazy view lyrically is supported by some hazy combination of instrumentation. The backing band here is on fire, providing Dylan a perfect and consistent backdrop with which to paint on. Listening to this record, you realize that Dylan paints in a similar fashion with each song, which ensures cohesion in the record. Proper flow? Check. Every track seamlessly flows into one another, with the proper amount of pacing from the open to the close. Done. No need to explain any more. IF you think I do, you have head issues. Not to offend, but seriously. This record is perfect in every way.

2. The Beatles - Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

You really can't write anything original about this record because it's already been said. It's an immaculately crafted concept album, thus satisfying every criterion. Next.

3. The Band - Music From Big Pink

No, no weak tracks here. Super-hit (and therefore maligned for its pervasive appearance in popular culture) with "The Weight." "Chest Fever" grooves just as good as James Brown, while the ballads like "In A Station" and "Lonesome Suzie" are impeccably powered along by Richard Manuel's angelic singing. This record is cohesive in that it essentially is representing America and its rural and core values (see my previous entry on the Band, titled It Must Be the Beards: "America" and "Common Sense" in Rock Music). And it flows lazily from one track to another, never hurrying but never lulling the listener into stupor with impeccably timed more upbeat tracks, but since the Band's sound and vision is so united, the flow is never "off" ever during the record.

4. The Clash - London Calling

Weak tracks? No, you can't really say that there are any exceedingly weak tracks. While "Koka Kola" isn't exactly "Rudie Can't Fail" or "London Calling," it's certainly not chaff, because it's an essential pastiche that plays an integral role in the record. You also have the major hit factor with both "Train In Vain (Stand By Me)" and "London Calling," so there's that criterion checked off. A cohesive view? I would argue that. It seems stylistically all over the place. There's heavy reggae influences in "Guns of Brixton" to the roar of the blues rip-off "Brand New Cadillac" to the light bar jazz of "Jimmy Jazz" (I swear that wasn't intentional). But the cohesive view? Punk has no boundaries. Punk is an aesthetic unbounded by genre and style and sound. The claim is that punk is capable of everything. And I think they accomplished it. The flow is certainly there, with enough energy to instill fear into the hearts of the ignorant and enough "downtime" (though I wouldn't really call it such) to allow for recharging before taking up the crusade once again.

5. The Beach Boys - Pet Sounds

This is also one of those records that is almost impossible to write about now. Flawless, stunning, and perfect in every way, it is an encapsulation of the innocence of youth, growing up (but sincerely not really wanting to), and the fond reminiscence of those youthful days where all that mattered was "you" and "me."

So there you go. There are countless albums that can be considered pretty perfect, but these five stand tall, heads and shoulders above the rest. Always and forever. It is highly unlikely that any record from here on out will conjure up the same effects on listeners that those five records have had on the rock and roll soundscape. For better or for worse, those records cast a shadow on everything else that has ever been and will ever be released.

Recent Record: Serge Gainsbourg - Histoire de Melody Nelson

Let me begin by tracing the extremely long and convoluted path that I took to finally listen to this record. Pitchfork has been gleefully documenting some strange Beck vs. Matt Friedberger vs. Radiohead fight thing. And then there's this whole Beck doing stuff with Charlotte Gainsbourg. And being curious I consulted everyone's friend, Wikipedia to find that she's the daughter of crazy Frenchman Serge, who I'd heard a bit about but had never been inclined to listen to. And voilà! Here we are. I've listened to this record, and with a little bit of backstory, here is my opinion on it:

This record is straight up funk-sounding. It grooves especially hard, trying to get you to feel it too, and groove along with it. And it does get you to groove along rather tastefully. This funk element is married to swooping string portions, which in some strange way works well on all levels. It's quite rare to find that strings and "funk"-based sound work together (if anything, it should join funk and horn sections), but Serge Gainsbourg deftly combines the two in an enjoyable manner. These funkier tunes are artfully balanced with softer, more traditional "pop" songs that accordingly play to Serge's strengths.

I will admit I have no understanding of French. But my research indicates that the lyrical material is quite racy. The general plot is that a much older man, in his fancy car, unexpectedly hits a girl on a bike. Said older man seduces said girl (Melody Nelson, hence the record), they do their sexual things (hear "En Melody" and her, uhm, cries of pleasure), and then she inevitably dies in a plane crash. For one reason or another.

What I get from my zero understanding is that this guy that Serge is portraying is a total player. And he sounds like it. He comes off as slightly sleazy, in some strange manner, and I'm going to guess that was the intended effect. And when taken on the whole with what is going on, it works. While on the "funkier" tracks Serge sounds like a total seduction-machine doing his thing, he sounds rather genuine in his affection. And this is through virtually no change in inflection. Perhaps it is a simple indicator that it's really the music behind the vocals that can change a mood entirely, but taken on the whole the feeling that something deeper is responsible is present.

I do like this record quite a bit. It's insanely catchy, and though I do feel oddly sleazy and/or dirty while listening to it, Histoire de Melody Nelson is, quite obviously, a very accomplished record. While those without experience with the French language (i.e. me) cannot really decipher what is going on story-wise (as the record is essentially a concept record), it really takes no time at all to get a sense of the goings-on just through what the band and Serge Gainsbourg himself are doing, whether it be affecting pop-crooning or funky seduction. The record is a great example of pop perfection, and as such I highly recommend getting around to this record if at all possible.

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Greatest Game of All Time: A Temporary Divergence

...and your first question is, no music discussion? I say, read my very very first entry, not everything is about music. I'm actually quite surprised that it took me this long to write a non-music topic. BUT I found a discussion of "greatest game of all time" as an entry on the Relevant website ("Question of the Day" a little while back) and I was astounded by the amount of, well, terrible responses. Gaming has always been my little secret hobby (not too secret, I suppose). I play a lot of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare (NO, I HAVE NOT GOTTEN MODERN WARFARE 2 YET, THANKS FOR ASKING >;( ). A whole lot. Back to the main point though, I sincerely love the Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time as much (actually, probably more) as/than the next person. It is, in fact, my second favorite game of all time. But it still stands miles and miles under this masterwork:

Resident Evil 4 is quite simply the greatest game of all time. No questions asked. Don't even worry about it. But to indulge you:

Resident Evil 4 is quite simply the greatest game of all time. No questions asked. Don't even worry about it. But to indulge you:

Perhaps in the context of the Resident Evil franchise, the fourth installment completely changed the game. The problem was that with the third installment, Nemesis, the side-shoot Code: Veronica, and the prequel ø, the franchise was beginning to stagnate. The pace of play was way too slow. The gameplay really dictated that. The puzzles were sometimes frustrating. I mean, you're getting chased by zombies, and it seems strange that you need "Ruby Jewel" to stick into a statue to proceed. But that is not meant to denigrate the previous entries, as they were all fantastic in their own right. Those problems weren't only a part of the Resident Evil problem, they were a part of the problem for the survival horror genre (see: Silent Hill series).

But something had to change, and change it did. Gone were the tank controls (and if you've played with them, oh, dear, how terrible), replaced with much more capabilities for smoother interactions with the environment and your bad guys. The puzzles? Not really there anymore. Sometimes you find some keys and pieces, but it's always a straightforward application rather than a long moment to ponder where "obscure piece A" is supposed to go. What happened? The gameplay was sped up. Enemies moved faster. You moved faster. It changed survival horror for the best (or for the worst, depending on your feelings for the genre).

The point is, the gameplay is intense and visceral. There are the small spaces where you freak out because a zombie guy (though in this particular Resident Evil entry, "zombie" is certainly a stretch on the normal term) has caught you in a corner. Or maybe because a crazy potato-sacked head man with a chainsaw is out to get your butt. Or maybe because you face severely long odds. Resident Evil 4 is essentially an action game. Everything is flawless.

There were several revolutionary points in the game, some meant for the franchise, the genre, but some even for gaming on the whole. For the franchise and genre, it meant the death of the slow pace of play. Given the clime (hello, Halo!), a slow pace of play wasn't really suitable. The controls were updated to suit the genre and franchise while still retaining the elements that made survival horror, well, survival horror. Small, enclosed areas, dark rooms, lots of zombies, insane plotlines, all those were still there. You were just walking the path perhaps a little quicker than imagined. But the game itself is so rich that even the fastest players still take 15 hours to complete it (I've played this game enough to be counted in that category).

On the "global" level, though, Resident Evil 4 introduced the "QTE," or "quick time event," into the game designer's arsenal. The essence is that any action can yield a QTE, wherein you get a cue for an event, and the player must quickly respond and press a button to continue on. This ranged from a cue to suplex a zombie and smash his face off, to surviving cinematic sequences (that was the real clincher). The cinematic sequences with QTEs really expanded the game atmosphere. It's sort of difficult to make the game interactive when your camera is normally stuck behind the character but the whole point of an event is to run away from a boulder coming from behind. So you flip the camera, make it a QTE, make the player frantically mash buttons to survive. Your problem of an entirely uninteractive scenario quickly became something not only interactive, but also engrossing and actually quite freaky.

The key here is that you involve your gamers in the cinematic sequences. In the majority of games, cue cinematic sequence, and boom! you lose your gamer, because a good percentage of players just want to play the game. They frankly don't care if some peripheral character dies, it's no big deal. "Just give me the controls and I'll just kill them all," they'll say. Well, the QTEs correct this problem. Quick-time events force the player to pay attention throughout the cutscene, because if they don't, the player won't get a chance to revenge because guess what, they lost their head too. So it forces players to keep their wits about them, gets the player invested in the storyline and keeps them involved (your ultimate goal as a game designer, anyways). There's a particular cinematic sequence in Resident Evil 4 that is absolutely flawless in design with regards to QTEs, and you will know it when you get there, so I won't spoil it.

By no means was this game shabby in the graphics department. It was cutting edge for the time, and cutting edge for the Gamecube. I'm not the kind of gamer who particularly cares really for graphics unless it drastically affects gameplay (and it usually doesn't), so I won't discuss this too much, but it's really the details that count here too. From the little textures to the nice touches to your gruesome deaths (oh, trust me, they happen to everyone when it comes to Resident Evil 4), graphics were still given a lot of consideration.

And for the record, despite all these changes to the franchise, 4 is still unmistakably a Resident Evil game. For one, it still is involved in the same universe, but the same sort of goofy plot (and the dialogue, for those fans of the terribly cheesy Resident Evil dialogue) is still there. Let's face it, the whole "zombie" phenomena is unlikely in and of itself, so there's no point in reducing the problem to be something as realistic as possible. So people are injecting themselves with viruses, mutating into crazy stuff. It makes the bossfights larger-than-life, downright gross (the point), and when necessary, downright scary. To reduce the whole point of "zombies" into something realistic would have been terrible, and wisely, Capcom avoided that problem here. The problem seems just plausible enough for you to be involved, but it's so fantastical and outrageous that the game becomes fun, in a sense, because you're transported to some wacky world (also a goal of game design). So, a win there.

The problem with the game might just have been the distribution. It was Gamecube only before it got ported because they realized it was good enough to make boatloads of money (because it was that good). And even then it was just PC and PS2. It was around this time when everyone was getting on the XBox trend, and so few to no players in America, at least, played it. There were very few reasons to pick up a Gamecube, not only because of its "family"-oriented mindset, but because there just wasn't a great selection of games (Super Smash Bros. Melee, The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker come to mind as the two most worthy titles on the 'cube at the time). But for those who got to it (me, although supremely late and first on the Wii edition of the game) in some way, shape or form, can acknowledge this masterwork.

Now, there's always different strokes for different folks, but for those informed, this is typically a consensus top-20 of all time pick. For me, I definitely consider it the best game of all time. From the moment I started playing, I was transported into a different world. Gripping, intense, with utterly visceral, intuitive, and engaging gameplay, Resident Evil 4, in my humble opinion (as primarily a man of music), should really be crowned as the best video game of all time.

Resident Evil 4 is quite simply the greatest game of all time. No questions asked. Don't even worry about it. But to indulge you:

Resident Evil 4 is quite simply the greatest game of all time. No questions asked. Don't even worry about it. But to indulge you:Perhaps in the context of the Resident Evil franchise, the fourth installment completely changed the game. The problem was that with the third installment, Nemesis, the side-shoot Code: Veronica, and the prequel ø, the franchise was beginning to stagnate. The pace of play was way too slow. The gameplay really dictated that. The puzzles were sometimes frustrating. I mean, you're getting chased by zombies, and it seems strange that you need "Ruby Jewel" to stick into a statue to proceed. But that is not meant to denigrate the previous entries, as they were all fantastic in their own right. Those problems weren't only a part of the Resident Evil problem, they were a part of the problem for the survival horror genre (see: Silent Hill series).

But something had to change, and change it did. Gone were the tank controls (and if you've played with them, oh, dear, how terrible), replaced with much more capabilities for smoother interactions with the environment and your bad guys. The puzzles? Not really there anymore. Sometimes you find some keys and pieces, but it's always a straightforward application rather than a long moment to ponder where "obscure piece A" is supposed to go. What happened? The gameplay was sped up. Enemies moved faster. You moved faster. It changed survival horror for the best (or for the worst, depending on your feelings for the genre).

The point is, the gameplay is intense and visceral. There are the small spaces where you freak out because a zombie guy (though in this particular Resident Evil entry, "zombie" is certainly a stretch on the normal term) has caught you in a corner. Or maybe because a crazy potato-sacked head man with a chainsaw is out to get your butt. Or maybe because you face severely long odds. Resident Evil 4 is essentially an action game. Everything is flawless.

There were several revolutionary points in the game, some meant for the franchise, the genre, but some even for gaming on the whole. For the franchise and genre, it meant the death of the slow pace of play. Given the clime (hello, Halo!), a slow pace of play wasn't really suitable. The controls were updated to suit the genre and franchise while still retaining the elements that made survival horror, well, survival horror. Small, enclosed areas, dark rooms, lots of zombies, insane plotlines, all those were still there. You were just walking the path perhaps a little quicker than imagined. But the game itself is so rich that even the fastest players still take 15 hours to complete it (I've played this game enough to be counted in that category).

On the "global" level, though, Resident Evil 4 introduced the "QTE," or "quick time event," into the game designer's arsenal. The essence is that any action can yield a QTE, wherein you get a cue for an event, and the player must quickly respond and press a button to continue on. This ranged from a cue to suplex a zombie and smash his face off, to surviving cinematic sequences (that was the real clincher). The cinematic sequences with QTEs really expanded the game atmosphere. It's sort of difficult to make the game interactive when your camera is normally stuck behind the character but the whole point of an event is to run away from a boulder coming from behind. So you flip the camera, make it a QTE, make the player frantically mash buttons to survive. Your problem of an entirely uninteractive scenario quickly became something not only interactive, but also engrossing and actually quite freaky.

The key here is that you involve your gamers in the cinematic sequences. In the majority of games, cue cinematic sequence, and boom! you lose your gamer, because a good percentage of players just want to play the game. They frankly don't care if some peripheral character dies, it's no big deal. "Just give me the controls and I'll just kill them all," they'll say. Well, the QTEs correct this problem. Quick-time events force the player to pay attention throughout the cutscene, because if they don't, the player won't get a chance to revenge because guess what, they lost their head too. So it forces players to keep their wits about them, gets the player invested in the storyline and keeps them involved (your ultimate goal as a game designer, anyways). There's a particular cinematic sequence in Resident Evil 4 that is absolutely flawless in design with regards to QTEs, and you will know it when you get there, so I won't spoil it.

By no means was this game shabby in the graphics department. It was cutting edge for the time, and cutting edge for the Gamecube. I'm not the kind of gamer who particularly cares really for graphics unless it drastically affects gameplay (and it usually doesn't), so I won't discuss this too much, but it's really the details that count here too. From the little textures to the nice touches to your gruesome deaths (oh, trust me, they happen to everyone when it comes to Resident Evil 4), graphics were still given a lot of consideration.

And for the record, despite all these changes to the franchise, 4 is still unmistakably a Resident Evil game. For one, it still is involved in the same universe, but the same sort of goofy plot (and the dialogue, for those fans of the terribly cheesy Resident Evil dialogue) is still there. Let's face it, the whole "zombie" phenomena is unlikely in and of itself, so there's no point in reducing the problem to be something as realistic as possible. So people are injecting themselves with viruses, mutating into crazy stuff. It makes the bossfights larger-than-life, downright gross (the point), and when necessary, downright scary. To reduce the whole point of "zombies" into something realistic would have been terrible, and wisely, Capcom avoided that problem here. The problem seems just plausible enough for you to be involved, but it's so fantastical and outrageous that the game becomes fun, in a sense, because you're transported to some wacky world (also a goal of game design). So, a win there.

The problem with the game might just have been the distribution. It was Gamecube only before it got ported because they realized it was good enough to make boatloads of money (because it was that good). And even then it was just PC and PS2. It was around this time when everyone was getting on the XBox trend, and so few to no players in America, at least, played it. There were very few reasons to pick up a Gamecube, not only because of its "family"-oriented mindset, but because there just wasn't a great selection of games (Super Smash Bros. Melee, The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker come to mind as the two most worthy titles on the 'cube at the time). But for those who got to it (me, although supremely late and first on the Wii edition of the game) in some way, shape or form, can acknowledge this masterwork.

Now, there's always different strokes for different folks, but for those informed, this is typically a consensus top-20 of all time pick. For me, I definitely consider it the best game of all time. From the moment I started playing, I was transported into a different world. Gripping, intense, with utterly visceral, intuitive, and engaging gameplay, Resident Evil 4, in my humble opinion (as primarily a man of music), should really be crowned as the best video game of all time.

Thursday, November 12, 2009

Revisited: Top 20 Albums of 2000-2009

No, my good friends, there is no rest for the weary. Even after initially publishing my list in August, I was still out on the hunt to make sure I constructed a good list, and alas! I did not. But most of the placements were right. With more research, I have been able to compile an even better list. However, this time I have chosen not to write blurbs about each entry, mostly out of sheer laziness (I call it nihilism for the whole process of journalism, mind you). But you, the reader, should use it as an excuse to listen to any of the records that you have not heard of. The majority of entrants in the previous entry suffered a drop in the rankings given an expansion to twenty albums, but the harshest fall was Loretta Lynn, bless her soul. But there were better records of the decade than that (and it doesn't age as well as I'd previously imagined), so I therefore must accommodate. Here goes:

1. Arcade Fire - Funeral

2. Wilco - Yankee Hotel Foxtrot

3. Radiohead - Kid A

4. Brian Wilson - SMiLE

5. OutKast - Stankonia

6. Bon Iver - For Emma, Forever Ago

7. Daft Punk - Discovery

8. Joe Strummer & the Mescaleros - Streetcore

9. The Avalanches - Since I Left You

10. Jay-Z - The Blueprint

11. The Strokes - Is This It

12. Animal Collective - Merriweather Post Pavilion

13. Modest Mouse - The Moon & Antarctica

14. Bob Dylan - "Love & Theft"

15. The White Stripes - White Blood Cells

16. Kanye West - Late Registration

17. LCD Soundsystem - Sound of Silver

18. Sigur Rós - Ágætis byrjun

19. Sufjan Stevens - Illinois

20. Fleet Foxes - Fleet Foxes

Note: There is a special Thanksgiving edit, because I forgot Daft Punk - Discovery, and I remembered.

1. Arcade Fire - Funeral

2. Wilco - Yankee Hotel Foxtrot

3. Radiohead - Kid A

4. Brian Wilson - SMiLE

5. OutKast - Stankonia

6. Bon Iver - For Emma, Forever Ago

7. Daft Punk - Discovery

8. Joe Strummer & the Mescaleros - Streetcore

9. The Avalanches - Since I Left You

10. Jay-Z - The Blueprint

11. The Strokes - Is This It

12. Animal Collective - Merriweather Post Pavilion

13. Modest Mouse - The Moon & Antarctica

14. Bob Dylan - "Love & Theft"

15. The White Stripes - White Blood Cells

16. Kanye West - Late Registration

17. LCD Soundsystem - Sound of Silver

18. Sigur Rós - Ágætis byrjun

19. Sufjan Stevens - Illinois

20. Fleet Foxes - Fleet Foxes

Note: There is a special Thanksgiving edit, because I forgot Daft Punk - Discovery, and I remembered.

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Music Progenitor: The Velvet Underground

There are a few things certain in life: the Beatles are likely the best band to ever exist in rock and roll, but the Velvet Underground were likely the most influential band to ever exist in rock and roll. Now "hold on!," you might say. I admittedly have only recently come of this opinion. I still am of the belief that the Beatles invented most forms of popular music today. But a lot of their territory is gone in my mind because the Velvets simply did it better. Because, let's be frank: the Beatles were master popsmiths. If it didn't have a good melody, it wasn't worth it to them. And thank God for that, because they had a fucking ear for melody. But the seedy underbelly, the counter-culture, the reverse flow of music, that oft-forgotten side...that was the area the Velvets held tightly in their grasp.

If you thought the Beatles were already sort of counter-culture, boy, you're in for a surprise. The Velvets, with their first two records, pushed every boundary imaginable. No topic was left untouched as a lyric. "Heroin" was a literal description of, well, doing heroin, while the cryptic "Venus In Furs" documents a tale of sexual deviance. "The Gift" was a spoken word tale of a boy mailing himself to his girl only to get killed waiting to get out of the box. This wasn't your normal stuff...no way. This was 1967, and even the Beatles never dared to venture this far with their lyrical exploration. The Velvets initially got a lot of crapola for their exploration of social deviance, but in retrospect it sincerely opened the door for virtually any artist to explore deviance in a meaningful way.

But on the music side, they pushed the envelope in many ways. The most striking thing about the Velvet Underground & Nico is the use of the viola. John Cale's experimentalism really drove the band forward within the first two records, and on the first record, it's through that viola. Instead of crafting elegant lines or whatever most people think a nice old viola should do, John Cale used the viola to create drones and a prickly bed of thorns for the rest of the band to play over...on the aforementioned "Heroin" and "Venus In Furs," those drones set the tone for the music and bring an intensity that could not have been constructed otherwise.

On White Light/White Heat, their experimentalism came from what John Cale had once called a quest for "anti-beauty." On the 15+ minute epic "Sister Ray," the apparent goal was to simply play louder than each other, with John Cale's organ fighting with Lou Reed's and Sterling Morrison's guitars, Moe Tucker's drums, and Lou's vocals, all the pieces (sort of) eternally locked in a battle to be the loudest. Previously mentioned "The Gift" is a spoken word piece, with the voice panned to one side and the instruments to the other, and in its strange way if you wanted to listen to an audiobook, you listened to the left channel, but if you wanted a jam, put in the right channel. Or you could, you know, put in both and enjoy it. But it was those little bits of experimentalism that made the record.

But the noise, oh, the noise. "I Heard Her Call My Name" is the prime example. Lou Reed's guitar runs wild like a depraved animal, squalling, sometimes off-key, deranged and self-destructive. But that was the point. It's so visceral, it rips you and forces you to listen, to be as raw as they were then. The sort of "guitar squalling feedback crazy weird solo" pops up time and time again in rock music, and it started here. You know, though, no one ever exerted less restraint with their solos than the Velvets did, and for that they proved to be the most dangerous and perhaps the most affecting.

I have vouched for the Velvets for their experimentalism, but they were not to be completely outdone on the pop front. Lou Reed knew how to write a good song, with catchy hooks aplenty. He just never indulged in it. They're seen early on in the Velvet Underground & Nico tunes "I'll Be Your Mirror" and "Sunday Morning," but until their third self-titled, it was never apparent. The Velvet Underground is a disarmingly quiet record, with not even a bit of feedback in sight. Every song except for "The Murder Mystery" (which is strikingly similar to "The Gift" but with many more interacting parts in it) is a bona fide pop masterpiece, from the mantra-like "Jesus" to the Factory-dedicated "Candy Says."

And then there's Loaded. Finally recognized for his pop sensibilities, Lou Reed was given a budget to sound like a pop star, and finally given a bit of production muscle, the record is, well, loaded with (potential) hits, with "Sweet Jane" and "Rock & Roll" actually becoming quite popular. It's a classic pop record, meaning that the Velvets were actually quite impressive pop auteurs...they just chose to not take the beaten path to get there.

Those familiar with Velvet lore know that Cale left the group ("ushered" out, whatever, it doesn't make much of a difference) after White Light/White Heat, thereafter replaced by Doug Yule. The word on the street is that this change from an experimentalist to another pop auteur changed the balance in the band. No one knows if this is true, but if it is, so what? The Velvets were an all-around damn good band regardless of form (mostly). Take it for what it's worth. They paved the way for experimentalists with the first two records and showed how anyone can write a good pop record with the last two...and no Squeeze IS NOT, IS NOT IS NOT a Velvet Underground record. It's just not. Don't even bother.

The argument then is that Lou Reed was the heart and soul of the Velvet Underground...and I'd have to agree.

But on their influence? The Velvets were proto-punk. See how "I'm Waiting For The Man" churns along, with Lou's sort of sneer-ish voice providing a groundwork for the nihilism of early punk. Their lyrical exploration empowered punk to do the same. While in a sense with all the instrumental experimentalism brought forth by the Velvets was dismantled by the punk bands, the point is still there. Post-punk titans Joy Division covered "Sister Ray" in some of their shows (not as long as the Velvets' original version, sure, but still a daunting task regardless). David Bowie loved the Velvets (and Lou Reed) so much that Bowie single-handedly revived Lou Reed's solo career with the Transformer record (a damn good one, when you think about it).

And the Velvets' influence is still around today. The Strokes have cited the Velvets as a key influence, and you can hear Casablancas do his best Lou Reed impression on their debut album, Is This It. The raggedy guitar solos done by Reed back in the day show up now and again, in works by Neil Young (his guitar-playing style is highly Velvet-ish, I would argue) to even Wilco (the cacaphony that surrounds the postlude to "At Least That's What You Said," with it's scraggly guitars and tense atmosphere can be traced to the Velvets at its core). Though they were decidely left-field, it's pretty obvious that the Velvets had a most widespread impact, creeping in and never letting go.

Convinced yet? I would hope so.

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

Post-Punk: The (Once) Wild Open West

In 1977, punk had basically already been declared dead. This was a strange claim to make, because the best of punk had yet to come (The Clash had not begun to flourish yet), but for whatever reason, the claim was made and essentially accepted. But this left a gaping hole in music at the time. Who now to guide music? Where would it go? This was answered by post-punk first, being particularly framed around the late 1970s to early 1980s, where it experienced the most success.

Punk was a format essentially thriving on (perhaps excessive) simplicity. If the construct was elaborate, it was torn down until it became uncomplicated. This allowed punk to serve as a format for political banter, fully embraced by many. But when punk was declared dead, this left many questions for those who came after. They wanted to remain true to those roots and be uncomplicated, but it was done before and, well, done as a genre. So where to go? A composite look at three bands answers that question. Talking Heads, Television, and Joy Division all together form basically the whole picture of the post-punk movement, with each band taking post-punk in a unique direction. What they all really had in common was their origins: they all loved punk, but when punk had died they all were left with no guide, and each forged their own unique identity to enter rock lore.

Talking Heads came from New York, fueled by the peculiar styling of David Byrne. As with all the groups, they began playing primarily derivatives of rock music, but even then they showed flashes of greatness, from "Psycho Killer" on their debut disc to the grandiose "The Big Country" and the sly reading of Al Green's "Take Me To The River." But with their next disc they began to explore what made them great (and different from the other post-punk groups); their love and therefore application of African polyrhythms led them to their creative peak, culminating in the masterful and essential Remain In Light record.

While Fear of Music represented a great stride forward with regards to generating their "sound," it was not until Remain In Light when it all came together. Drawing heavy influence from African music-making, from the unique polyrhythms to even the way they wrote and constructed the music, Talking Heads, with the guiding hand of Brian Eno, created an entirely new sound. The music was about the composite experience, not just the individual parts, utilizing only one chord throughout the song and let all the rhythms set by the percussion, the bass, the guitars, and even Byrne's voice do the lifting...in unison. What makes the record so disarming is its restlessness, from Byrne's wandering, stream of consciousness lyrics to the undulating rhythms that drive each track to both everywhere and nowhere at once. Parts weave in and out, interact with each other as they float into the mixes for periods of time before mysteriously fading out. Suffice to say, this was one of the three peaks of post-punk, but to belabor the point on Remain In Light and Talking Heads in general seems to be a disservice.

The other great American post-punk band was simply named Television, hailing once again from New York City. While Talking Heads found their mine of gold through the integration of African polyrhythms, Television found their "sound" through the use of clever guitar interplay. The term "clever guitar interplay," however, really demeans and downplays what they accomplish on their flagship record, Marquee Moon (pictured above).

The album is basically the guitar player's Bible. There is not a note wasted, not a note poorly spent. It essentially made the claim that technicality in guitar playing was, well, merely a technicality. Dismissive of the pervasive "über-playing" of flashy blues players, Television successfully said that a bunch of fast notes played together hardly makes a solo or even a song. Each riff is meticulously planned, with each guitar weaving in and out of each other in perfect unison, complementary yet totally unique. There is a genuine sense of shape and melody with each line that each guitar plays, from the gradual buildup into epic moments on masterwork "Marquee Moon" to the cascading riffs that permeate "Friction."

But because Marquee Moon is the guitar player's Bible does not mean that any of the other qualities are readily discarded. Tom Verlaine is at his most mysterious here, and the geeky (and nifty) interplay between him and his band-mates on tracks such as the rollicking opener "See No Evil" and its follower "Venus" give the record the many little moments that can still shine on an album dominated primarily by the fantastic guitar work presented. Before Television came about, guitar playing was primarily about virtuosity and the ability to be technical, but in one fell swoop, the game was utterly rewritten.

The only Brits to significantly affect post-punk were a quartet of lads from Manchester known as Joy Division. Joy Division encountered a stranger route to success. Originally a rather blasé and not very unique band that played with the typical punk-influence, Joy Division did not come upon their style until they detached themselves from the time-honored tradition of playing at ludicrously fast tempos and slowed down. Only then did Joy Division find their niche and become wholly intense, visceral, and become, well, Joy Division. And what resulted were two of the most essential records in any person's music catalog.

Frankly, I don't wish to elaborate too in depth on each record, but the reason why Joy Division really separated themselves from the rest of the post-punk pack was the emphasis on ambiance and atmosphere, leaving space rather than filling it. While live they displayed none of the "ambiance" parts (instead becoming particularly ragged and aggressive in a live setting), their use of ambiance and atmosphere in the studio essentially defined genres to come. Perhaps primarily attributed to their choice of producer, Martin Hannett, Joy Division were pushed to entirely new levels of art. Combining the unique "cold" production (and if that term does not make sense, listen to the record and within one second of the record beginning you will understand) with the sheer muscle of the band, two masterpieces, Unknown Pleasures and Closer were born.

The only downer point, ever, on Joy Division is that, well, Ian Curtis was a bit of a downer himself. The lyrics are essentially depressing, and without a doubt they forecasted the bitter end that Ian Curtis would face (for those unfamiliar, he committed suicide before Closer was ever released). But Ian Curtis was a lyrical genius endlessly battling the depression that came from crippling epileptic attacks and a failing marriage. His lyrics, as surely as anything, reflect this, but never were his lyrics your typical "depresso" lyric style; never wallowing in self-pity as most often do, he altogether emphasized alienation and a genuine sense of loss that came as real. One can really only imagine what Joy Division would have been capable of if Ian Curtis were still around.

------

Taken together, Talking Heads, Television, and Joy Division all came to symbolize what post-punk did quite right, though none lasted very long. It would be inherently easy to dismiss each group, perhaps, on their short existences as groups, but to simply call them "flashes in the pan," given the work they did, is a gross oversight and misunderstanding. Perhaps through tragedy or strife, none of the groups (and the genre itself) made it beyond several years. But the relics they left behind, those records, all serve as time-worn monuments to the genre of post-punk that would go on the become a pervasive influence in alternative rock.

Punk was a format essentially thriving on (perhaps excessive) simplicity. If the construct was elaborate, it was torn down until it became uncomplicated. This allowed punk to serve as a format for political banter, fully embraced by many. But when punk was declared dead, this left many questions for those who came after. They wanted to remain true to those roots and be uncomplicated, but it was done before and, well, done as a genre. So where to go? A composite look at three bands answers that question. Talking Heads, Television, and Joy Division all together form basically the whole picture of the post-punk movement, with each band taking post-punk in a unique direction. What they all really had in common was their origins: they all loved punk, but when punk had died they all were left with no guide, and each forged their own unique identity to enter rock lore.

Talking Heads came from New York, fueled by the peculiar styling of David Byrne. As with all the groups, they began playing primarily derivatives of rock music, but even then they showed flashes of greatness, from "Psycho Killer" on their debut disc to the grandiose "The Big Country" and the sly reading of Al Green's "Take Me To The River." But with their next disc they began to explore what made them great (and different from the other post-punk groups); their love and therefore application of African polyrhythms led them to their creative peak, culminating in the masterful and essential Remain In Light record.

While Fear of Music represented a great stride forward with regards to generating their "sound," it was not until Remain In Light when it all came together. Drawing heavy influence from African music-making, from the unique polyrhythms to even the way they wrote and constructed the music, Talking Heads, with the guiding hand of Brian Eno, created an entirely new sound. The music was about the composite experience, not just the individual parts, utilizing only one chord throughout the song and let all the rhythms set by the percussion, the bass, the guitars, and even Byrne's voice do the lifting...in unison. What makes the record so disarming is its restlessness, from Byrne's wandering, stream of consciousness lyrics to the undulating rhythms that drive each track to both everywhere and nowhere at once. Parts weave in and out, interact with each other as they float into the mixes for periods of time before mysteriously fading out. Suffice to say, this was one of the three peaks of post-punk, but to belabor the point on Remain In Light and Talking Heads in general seems to be a disservice.

The other great American post-punk band was simply named Television, hailing once again from New York City. While Talking Heads found their mine of gold through the integration of African polyrhythms, Television found their "sound" through the use of clever guitar interplay. The term "clever guitar interplay," however, really demeans and downplays what they accomplish on their flagship record, Marquee Moon (pictured above).

The album is basically the guitar player's Bible. There is not a note wasted, not a note poorly spent. It essentially made the claim that technicality in guitar playing was, well, merely a technicality. Dismissive of the pervasive "über-playing" of flashy blues players, Television successfully said that a bunch of fast notes played together hardly makes a solo or even a song. Each riff is meticulously planned, with each guitar weaving in and out of each other in perfect unison, complementary yet totally unique. There is a genuine sense of shape and melody with each line that each guitar plays, from the gradual buildup into epic moments on masterwork "Marquee Moon" to the cascading riffs that permeate "Friction."