Wednesday, October 27, 2010

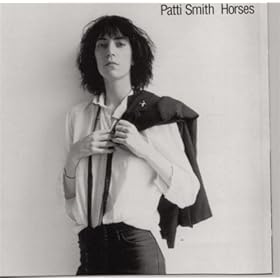

Rapid Reaction: Patti Smith - Horses

I suppose the good question is this: how did it take me so long to get to this record? And my answer is this: I sincerely don't know. It's got all the connections that would put it on my radar: John Cale produced this, it counts as proto-punk, Tom Verlaine played on the record and you can connect Van Morrison and the Smiths to this. I realize that my position pretty indefensible...there is no real excuse for not hearing this until now, but at least I've now rectified that mistake.

I've listened to it once and am currently working through it the second time as I write this, and I can honestly say it deserves all the cred it gets: it's a masterwork. It's one of those records that will blow your mind open; it blasts your brains, picks up the pieces and reforms your brain into something new. All from the first note.

Aside from the intro to "Gloria" that slinks in before it makes its presence known, the record is a ball of fury and energy, and if you're not getting blitzed by the energy in the proto-punk sound, you're getting blitzed by her lyrics, which are part beat poetry and part stream-of-consciousness not unlike the master himself, Bob Dylan. The sound has a proto-punk roar that hangs around the big guys like the Velvet Underground, and Patti Smith sounds like an extremely angry cross between Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. The passion in this record doesn't just seep out and let you "sort of" feel it: the amount of passion in this record is explosion-inducing and you feel it. And if you don't, you're not alive. Plain and simple.

I don't know how else to put it. This record is a force of nature. And it's one to behold. I'm sure a lot of others have been able to wax more poetic about it than I have, but maybe that would do the record an injustice, as it's so stripped down and bare in its proto-punk approach, that to speak more about is contrary to the spirit of the record. It's one that has to be heard to be believed.

Friday, October 15, 2010

Spirituality and Music, redux

Two entries in two days?!? I am finally starting to get back into the swing of things, apparently. Homework beckons, but my thoughts beckon more...

---------------------

You can search for my old entry (about a year old) and see that I railed quite heavily on the genre of Christian rock music for its faults. It was because quite frankly, it is still true to a great extent. I still find Christian rock to be rather pedestrian and unimaginative, but as I've recently been trying to live out the penultimate words of George Harrison ("Everything can wait, but the search for God cannot wait."), I perhaps may have judged the genre too harshly. It is worship music, and despite my perception of it, people still connect to it and through it to that higher plane, so it must therefore hold some value. And as everyone knows, music is one of the most subjective fields, so when it comes to trying to organize it and present it in a remotely academic manner there is bound to be some oversight, and I am "being the bigger man" in admitting to some of that.

But that does not mean that I am totally recanting my statement. It just means that I previously undervalued it. What made me reconsider my stance was something the legendary Mavis Staples said when interviewed on the Colbert Report. When asked about her reasons for moving from gospel to soul in the 1960s (and her thoughts about the cries of "traitor" it generated from the community), Mavis essentially said: "All music glorifies God." While I'm unsure if she is familiar with Slayer, one realizes it is essentially true. And it simply goes beyond any religious notions. Whether or not one believes in the vehicle of God or otherwise, music is inherently powerful and it showcases the unique power that humanity has, in weakness and in strength. Whether it is worship music or gleefully skewering religion (see: "Highway 61 Revisited" for a particularly delightful roasting of the Abraham story), it all essentially carries infinite power and meaning. That is what makes music, well, music.

I still think that Christian rock has quite a-ways to go if it wants to be considered as proficient in the "academic" and "quality" sense I have been trying to impart. If I may continue tooting this particular horn, it is so pre-occupied with presenting the message of Lord without realizing that the music itself is already the message! Music already glorifies the Lord, so if you simply strive make good music, you are already completing your objective! Now, this is not obvious to most people, so I understand that perhaps in needing to spread their message they are tempted to brandish a big stick, but that is what makes the music so pedestrian to me. The music becomes clumsy and unimaginative when the only thing music has is to be graceful and imaginative! I don't necessarily mean this in the technical-playing sense (thus punk would be ruled out, and we all know punk has too much heart and balls of steel for that), but in the artistic, striving-for-quality sense. As evidence, I present the best "worship" record of all time, in my opinion:

A Love Supreme is beyond a masterwork: it is a monolith of the power of music, standing tall as a man among boys. Far and away the best jazz record of all time (it would most certainly rank in my top 20, if not top 10 records of all time), it is a testament: to Coltrane's power, to Coltrane's skill, to Coltrane's faith. Coltrane made the record to demonstrate his faith and his love for his Lord. The devotional poem in the liner notes is "recited" via his saxophone in the last movement, with the final lines in that poem showing his love for God:

"Elation. Elegance. Exaltation. All from God. Thank you God. Amen."

The record is overbearing only in that it is overbearingly perfect. It does not wield its faith like a stick to beat home the point, but the faith is implemented like a fine knife used to carve the most detailed of sculptures. The search for quality in the music mirrors Coltrane's search for God, and in both Coltrane finds what he had been looking for. It doesn't matter if you aren't a believer or not in Coltrane's faith. The music contains so much of that often-sought "soul" that by the end of the record you believe: if not in his faith or his skill, you will at least believe in the power of music.

And it reinforces the point I have been trying to hit home in this entry: the power of music is the power of that higher plane. Take care of the first and the rest will follow. It is something that Christian rock would do well to heed if it wants to reinforce its connection to the Lord and actually serve as quality music. Under the "Mavis Staples assumption" (as I'll call it from here on out...assuming I ever refer back to it), any music is inherently worship music, so quality music is the highest worship music attainable. So strive for it. Music is a microcosm of life: if one stops searching for meaning and quality, then all is hopeless and futile.

-----------------------

If one needs proof that Christian rock needs to strive for quality once more, one only needs to realize that it was skewered rather successfully by South Park in the Season 7 episode "Christian Rock Hard."

---------------------

You can search for my old entry (about a year old) and see that I railed quite heavily on the genre of Christian rock music for its faults. It was because quite frankly, it is still true to a great extent. I still find Christian rock to be rather pedestrian and unimaginative, but as I've recently been trying to live out the penultimate words of George Harrison ("Everything can wait, but the search for God cannot wait."), I perhaps may have judged the genre too harshly. It is worship music, and despite my perception of it, people still connect to it and through it to that higher plane, so it must therefore hold some value. And as everyone knows, music is one of the most subjective fields, so when it comes to trying to organize it and present it in a remotely academic manner there is bound to be some oversight, and I am "being the bigger man" in admitting to some of that.

But that does not mean that I am totally recanting my statement. It just means that I previously undervalued it. What made me reconsider my stance was something the legendary Mavis Staples said when interviewed on the Colbert Report. When asked about her reasons for moving from gospel to soul in the 1960s (and her thoughts about the cries of "traitor" it generated from the community), Mavis essentially said: "All music glorifies God." While I'm unsure if she is familiar with Slayer, one realizes it is essentially true. And it simply goes beyond any religious notions. Whether or not one believes in the vehicle of God or otherwise, music is inherently powerful and it showcases the unique power that humanity has, in weakness and in strength. Whether it is worship music or gleefully skewering religion (see: "Highway 61 Revisited" for a particularly delightful roasting of the Abraham story), it all essentially carries infinite power and meaning. That is what makes music, well, music.

I still think that Christian rock has quite a-ways to go if it wants to be considered as proficient in the "academic" and "quality" sense I have been trying to impart. If I may continue tooting this particular horn, it is so pre-occupied with presenting the message of Lord without realizing that the music itself is already the message! Music already glorifies the Lord, so if you simply strive make good music, you are already completing your objective! Now, this is not obvious to most people, so I understand that perhaps in needing to spread their message they are tempted to brandish a big stick, but that is what makes the music so pedestrian to me. The music becomes clumsy and unimaginative when the only thing music has is to be graceful and imaginative! I don't necessarily mean this in the technical-playing sense (thus punk would be ruled out, and we all know punk has too much heart and balls of steel for that), but in the artistic, striving-for-quality sense. As evidence, I present the best "worship" record of all time, in my opinion:

A Love Supreme is beyond a masterwork: it is a monolith of the power of music, standing tall as a man among boys. Far and away the best jazz record of all time (it would most certainly rank in my top 20, if not top 10 records of all time), it is a testament: to Coltrane's power, to Coltrane's skill, to Coltrane's faith. Coltrane made the record to demonstrate his faith and his love for his Lord. The devotional poem in the liner notes is "recited" via his saxophone in the last movement, with the final lines in that poem showing his love for God:

"Elation. Elegance. Exaltation. All from God. Thank you God. Amen."

The record is overbearing only in that it is overbearingly perfect. It does not wield its faith like a stick to beat home the point, but the faith is implemented like a fine knife used to carve the most detailed of sculptures. The search for quality in the music mirrors Coltrane's search for God, and in both Coltrane finds what he had been looking for. It doesn't matter if you aren't a believer or not in Coltrane's faith. The music contains so much of that often-sought "soul" that by the end of the record you believe: if not in his faith or his skill, you will at least believe in the power of music.

And it reinforces the point I have been trying to hit home in this entry: the power of music is the power of that higher plane. Take care of the first and the rest will follow. It is something that Christian rock would do well to heed if it wants to reinforce its connection to the Lord and actually serve as quality music. Under the "Mavis Staples assumption" (as I'll call it from here on out...assuming I ever refer back to it), any music is inherently worship music, so quality music is the highest worship music attainable. So strive for it. Music is a microcosm of life: if one stops searching for meaning and quality, then all is hopeless and futile.

-----------------------

If one needs proof that Christian rock needs to strive for quality once more, one only needs to realize that it was skewered rather successfully by South Park in the Season 7 episode "Christian Rock Hard."

Thursday, October 14, 2010

What's (Not) Wrong With Electronica

Once again, supremely late, but once again I find myself unwilling to commit myself to sleeping (despite a severe lack of it) and so I finally now have the time to commit some of my thoughts once again...

-----------------

Yes, I've always considered older music to be infinitely better than what's out now. You get a true sense of soul from it, from Sam Cooke (i.e. Live at the Harlem Square Club 1963) to the wistful sighs of Richard Manuel and the way he, Rick Danko, and Levon Helm combine to tug at your heartstrings, there is always the sense of "soul" found in the recording. It speaks, it breathes character, exudes emotions. Those feelings are what let us connect to the music, and at least for me I find that older music fosters that in a much more meaningful way (let alone connect at all). Modern music just always seemed to lack that "soul" that would draw me to it. Until, perhaps, now.

Perhaps I had judged it incorrectly. Electronica/dance is a different beast compared to rock and roll (though it can certainly be an analogous construct): it must be evaluated on separate parameters. It's unlikely that electronica/dance will provide the payoff that, say, a Staple Singers track may provide with goosebump-causing moments, where Mavis and co. just pull off that moment of release with utmost mastery. However, electronica/dance still can contain soul, but it's not in the same way rock and roll often stakes its livelihoods in those climaxes (ahem...Sigur Rós). Electronica/dance contains "soul" once it establishes a beat: but it has to grab you from your "inner core," so to speak, and drive you to simply feel it. A true track would likely simply cause you to want, or even need, to dance.

Case in point? Daft Punk. They can be classified as French house, which is apparently separate from Detroit house, from all other sorts of electronica, but at least when it comes to mainstream/crossover appeal, no one has had more success than Daft Punk. And it's not especially difficult to see how and why.

Perhaps moreover known for being sampled by le Kanye West in his track "Stronger," it is impossible to deny that Daft Punk craft excellent tracks. From "Da Funk" to "Around the World," "Face to Face," "One More Time," and "Robot Rock," Daft Punk essentially have mastered their form of art. Their beats are uncomplicated, and perhaps therein lies the charm. They utilize basic beats but the layers above add the character to the track, allowing for someone to simply be "grabbed" and pulled into the song (and, perhaps, into dancing). Oftentimes, unlike other artists, they tend to emphasize the groove and tend to delve into "funk"-ier areas of existence, such as "Da Funk," which is essentially a clinic on how to groove like a master.

But it's really their live material where they shine. On Alive 1997, they essentially DJ for 45 straight minutes, rolling through such prime cuts like "Rollin' and Scratchin'," the oft-mentioned "Da Funk," among other tracks. The tracks are stretched, altered, and fixed up to match the length, with interludes and other bits providing perfect segues in between the more recognizable sections. Then, on Alive 2007, Daft Punk essentially provide a "Greatest Hits" DJ-mashup attack, smartly and cleverly combining tracks to provide new glances at them and give them a fresh context and meaning. "Television Rules the Nation" kicks off one track, and when combined with "Crescendolls" off of Discovery, gives both tracks strange new life as the tone of "Crescendolls" gets dramatically altered with "Television Rules the Nation" thumping under it. "Face to Face" is also a prime example of such as the disco feel in the backbeat is replaced by the "Harder Better Faster Stronger" theme, giving the song a fresh backdrop and also a subliminal meaning that gels quite nicely with the intent of "Face to Face" before it segues into "Short Circuit."

While I certainly love Discovery, Homework, and Human After All to death, it is impossible to say that Daft Punk aren't a better live machine than a studio machine. And that is saying quite a lot given that Discovery is at least a "masterwork +," Homework is a "masterwork" and Human After All is "reasonably good" (tracks off of Human After All benefit considerably on Alive 2007 with the mashups providing new context and life).

Regardless, after waxing at length about the prowess of Daft Punk, the point is this: after listening to them for awhile and finally getting into it, their records made me realize that perhaps electronica/dance could perhaps contain what I have always sought in music, that being "soul." It's not the same sort of "soul" as I had been searching for prior, and that is the likely reason why I hadn't found it; I simply wasn't looking in the right place for the "soul" of the work. Amidst all the rigidity in structure, form, and instrumentation, the "soul" was indeed possible in the energy of the work, that it infiltrates you and makes you unable of doing anything else but enjoying the work present.

I am no electronica/dance expert, but the existence of Daft Punk disproved my "technological advancement is bad for music" theory. I had figured it was a sure way to wipe the soul straight out of a work, but I was apparently wrong, as a compelling counter-argument has revealed itself. Daft Punk could perhaps be a rare exception to the rule, but an exception's existence makes the theory likely wrong. Further examination will likely have to follow. But that still doesn't mean that I prefer modern music to old-school music, it just means that I undervalued it.

PS. I have an odd question: is there EVER an inappropriate time to listen to Daft Punk? I thought so.

-----------------

Yes, I've always considered older music to be infinitely better than what's out now. You get a true sense of soul from it, from Sam Cooke (i.e. Live at the Harlem Square Club 1963) to the wistful sighs of Richard Manuel and the way he, Rick Danko, and Levon Helm combine to tug at your heartstrings, there is always the sense of "soul" found in the recording. It speaks, it breathes character, exudes emotions. Those feelings are what let us connect to the music, and at least for me I find that older music fosters that in a much more meaningful way (let alone connect at all). Modern music just always seemed to lack that "soul" that would draw me to it. Until, perhaps, now.

Perhaps I had judged it incorrectly. Electronica/dance is a different beast compared to rock and roll (though it can certainly be an analogous construct): it must be evaluated on separate parameters. It's unlikely that electronica/dance will provide the payoff that, say, a Staple Singers track may provide with goosebump-causing moments, where Mavis and co. just pull off that moment of release with utmost mastery. However, electronica/dance still can contain soul, but it's not in the same way rock and roll often stakes its livelihoods in those climaxes (ahem...Sigur Rós). Electronica/dance contains "soul" once it establishes a beat: but it has to grab you from your "inner core," so to speak, and drive you to simply feel it. A true track would likely simply cause you to want, or even need, to dance.

Case in point? Daft Punk. They can be classified as French house, which is apparently separate from Detroit house, from all other sorts of electronica, but at least when it comes to mainstream/crossover appeal, no one has had more success than Daft Punk. And it's not especially difficult to see how and why.

Perhaps moreover known for being sampled by le Kanye West in his track "Stronger," it is impossible to deny that Daft Punk craft excellent tracks. From "Da Funk" to "Around the World," "Face to Face," "One More Time," and "Robot Rock," Daft Punk essentially have mastered their form of art. Their beats are uncomplicated, and perhaps therein lies the charm. They utilize basic beats but the layers above add the character to the track, allowing for someone to simply be "grabbed" and pulled into the song (and, perhaps, into dancing). Oftentimes, unlike other artists, they tend to emphasize the groove and tend to delve into "funk"-ier areas of existence, such as "Da Funk," which is essentially a clinic on how to groove like a master.

But it's really their live material where they shine. On Alive 1997, they essentially DJ for 45 straight minutes, rolling through such prime cuts like "Rollin' and Scratchin'," the oft-mentioned "Da Funk," among other tracks. The tracks are stretched, altered, and fixed up to match the length, with interludes and other bits providing perfect segues in between the more recognizable sections. Then, on Alive 2007, Daft Punk essentially provide a "Greatest Hits" DJ-mashup attack, smartly and cleverly combining tracks to provide new glances at them and give them a fresh context and meaning. "Television Rules the Nation" kicks off one track, and when combined with "Crescendolls" off of Discovery, gives both tracks strange new life as the tone of "Crescendolls" gets dramatically altered with "Television Rules the Nation" thumping under it. "Face to Face" is also a prime example of such as the disco feel in the backbeat is replaced by the "Harder Better Faster Stronger" theme, giving the song a fresh backdrop and also a subliminal meaning that gels quite nicely with the intent of "Face to Face" before it segues into "Short Circuit."

While I certainly love Discovery, Homework, and Human After All to death, it is impossible to say that Daft Punk aren't a better live machine than a studio machine. And that is saying quite a lot given that Discovery is at least a "masterwork +," Homework is a "masterwork" and Human After All is "reasonably good" (tracks off of Human After All benefit considerably on Alive 2007 with the mashups providing new context and life).

Regardless, after waxing at length about the prowess of Daft Punk, the point is this: after listening to them for awhile and finally getting into it, their records made me realize that perhaps electronica/dance could perhaps contain what I have always sought in music, that being "soul." It's not the same sort of "soul" as I had been searching for prior, and that is the likely reason why I hadn't found it; I simply wasn't looking in the right place for the "soul" of the work. Amidst all the rigidity in structure, form, and instrumentation, the "soul" was indeed possible in the energy of the work, that it infiltrates you and makes you unable of doing anything else but enjoying the work present.

I am no electronica/dance expert, but the existence of Daft Punk disproved my "technological advancement is bad for music" theory. I had figured it was a sure way to wipe the soul straight out of a work, but I was apparently wrong, as a compelling counter-argument has revealed itself. Daft Punk could perhaps be a rare exception to the rule, but an exception's existence makes the theory likely wrong. Further examination will likely have to follow. But that still doesn't mean that I prefer modern music to old-school music, it just means that I undervalued it.

PS. I have an odd question: is there EVER an inappropriate time to listen to Daft Punk? I thought so.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)