So why do sex, drugs, and rock and roll seem to come hand in hand, kind of like how it's almost impossible to order the B without the L and the T, or any combination thereof? The most drugged out rockers seem to be most blessed with the gift of rock and roll: Keith Richards and Jimi Hendrix were infamous with their use of the horse (i.e. heroin), while others such as David Bowie and Iggy Pop were all about the blow (i.e. cocaine). But the drugs, in addition to sex, seem to always take precedence or even define the very nature of rock and roll: without the sex and the drugs, rock and roll would not exist at all today, in any way, shape or form. While hypothetical situations such as that can be debated, the bigger question is "why?" Why have sex and drugs shaped rock and roll as much as they have? I think the answer lies in the concept of euphoria.

Sex and drugs are able to foster the highest highs and the lowest lows in a person. Whether it be a most innocent affection or love (i.e. the Herman's Hermits classic "I'm Into Something Good"), a straight-out depiction of a trip (i.e. "Tomorrow Never Knows" by the Beatles), or something utterly raunchy (like Marvin Gaye's "Let's Get It On"), they all evidence the same feeling of euphoria, the same complete happiness with one's state. See also their flip-sides, those moments of pain due to the realization of lost love (Joy Division's masterwork "Love Will Tear Us Apart") the need for drugs (another masterwork, "Heroin" by the Velvet Underground), the evidence for why sex and drugs have been a vital part of the rock and roll livelihood and the basis for its mystique is because that sex and drugs typically bring out the happiest and the saddest in human beings. Euphoric joy when everything is going right thanks to love, sex, and drugs, and crippling depression when those things leave the rock and roll man with nothing left to live for.

The easiest full-blown examples of those highs and lows lie within the breakup albums: the best examples are Sea Change by Beck, Blood on the Tracks by Bob Dylan, Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs by Derek and the Dominos. Ok, so perhaps the last one is a stretch in that order, but if you were in love with your best friend's wife, I'd say that's about equivalent to a breakup, if not worse. They all evince the same themes: sheer joy, the throes of despair, it's all there, plain to see. While not really relating completely to the notion of drugs in rock and roll, the emotions they generate are inherently the same.

All the highs and lows would be useless if it weren't for the narrators who reveal the story, reveal the triumphs and the downfalls, and make us feel. Rock and roll is (usually) about wearing your heart on your sleeve, so we as listeners 100% identify with the narrator of the song, to live with (or through) them during both the good times and the bad; without the capacity to generate empathy, rock would be as cold and forbidding as electronica. Every emotion is completely represented in the rock and roll psyche, from hope for the best to the realization of dread, from the best party the night before to the raging hangover after: if it were not for the sex and drugs, then those emotions would not be as easy to channel into a rock and roll song, and today we would be left with a most infantile rock and roll genre of music, which would honestly be terrible, not only to say that this blog would likely be nonexistent if that were true.

That is not to say that sex and drugs are the only things that go together with rock and roll. Virtually anything could go together with rock and roll, given that it makes those rampant emotions easy to generate, bottle up and unleash in a rock and roll song. Sex and drugs are simply the easiest ways to tap into that reserve of our emotions and connect us to them, because they're things many of us have to grapple with. For example, gospel/worship music (I have somehow referred to them very often the past couple of entries when the previous year I'd not mentioned them at all) derives all its euphoric highs and debilitating lows from the relationship between the singer/listener and God. But for the non-religious, it's certainly harder for one to relate to their plight; whereas most everyone battles with sex and drugs, not everyone battles with the nature of their relationship with God.

For the rest of rock and roll's existence, it will probably still be forever bundled with sex and drugs. Probably for the better, sex and drugs more easily made emotions easier to access for rock and roll: the barest confessionals, the unabashed statements of love and the hilarious tales of hangovers or adventures would simply not exist without them. Am I implicitly condoning the rampant use of sex and drugs? I hope not, as excessive use of either is simply self-destructive. I'm merely pointing out that the history of rock and roll shows that for better or for worse, sex and drugs were tightly interwoven into the fabric of rock and roll, and perhaps in some ways as rock and roll glorified and brought out the best in sex and drugs, sex and drugs glorified and brought out the best in rock and roll.

Monday, November 22, 2010

Monday, November 15, 2010

The Power of the Rock Anthem

In my typically fine form, I'm choosing not to write about what I said I would write earlier. I chose to write this one instead because I can't get the chorus of Paul Stanley's "Live to Win" out of my head...the verses kind of suck, but the chorus sticks in your head and suddenly you yourself LIVE TO WIN!!! (no lie)... I suppose the fact that it's in South Park doesn't hurt its cause at all. That song just screams "rock anthem," and so here we are.

-------

Yeah, you can name 'em. Everyone recognizes them. From virtually every song by Bruce Springsteen to David Bowie's "Heroes," from "Hey Jude" by the Beatles (moreso the last mantra section) to "Sweet Virginia" by the Rolling Stones, rock anthems are powerful tools that are amazing because they inspire the listener and create such intense emotions in the listener so much as to create action, usually. Sometimes to even relate in music you need a rock anthem because their "sound," their energy, their spirit is a great unifier of people. This is why when a song like "Bohemian Rhapsody" comes on, everyone, and I mean everyone (unless you are so hipster that you choose to non-conform to such a tradition) goes full throttle into the song all through the end. True rock anthems are, quite simply, uniters and not dividers. So really, what distinguishes the rock anthem and what makes it so good?

The main ingredient in a rock anthem is usually the "sense of the epic." While this sounds broad, nondescript and generally useless, it's the best term to use. What may help illustrate my point, however, are examples of the "sense of the epic." Bruce Springsteen, as mentioned before, is essentially the king of the rock anthem, and one of his most widely known tracks, "Born to Run," illustrates the point. It sounds big. It goes for broke. The power in the song rattles you to your bones. His lyrics also display of a "sense of the epic, " painting desolation around but lo! the eternal ray of light that is worth pursuing prevails! For Bruce Springsteen's characters, it's quite simply a "do or die" moment and this sense of utmost importance and urgency imbues the song with a strong sense of power, direction, and purpose, not to mention an overall "sense of the epic."

Therefore, is there a sound that defines the rock anthem? I'd argue that there isn't, though the evidence seems to suggest the contrary. Tracks like the aforementioned "Heroes" (by Bowie), "Bohemian Rhapsody" or even "Wake Up" by Arcade Fire all have extremely ornate production. The layering of such a large quantity of instruments (an offshoot or spinoff of the "Wall of Sound") generates a large sound, hence the "sense of the epic" and hence a rock anthem. However, I would also posit that anthems such as "Sweet Virginia" by the Rolling Stones, "Hey Jude" by the Beatles, and other tunes like "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" all suggest that the rock anthem as a dense and layered concoction brewed in the studio may not be necessarily true, though the trend is evident and typically suggests otherwise.

For a rock anthem to truly succeed, the necessary portion is that of the chorus. If the chorus is not rally-worthy, then the song is not a rock anthem. It's the power in the chorus that makes the rock anthem such a uniter: who doesn't sing "BORNNNNN IN THE USAAAAAAAA-EAAAAAAA!!!!!!!" when it comes on? I rest my case. The chorus has to be easily accessible: even the layman must be able to get around to remember it, so that perhaps even in his drunkest hour he may be able to belt out the chorus when prompted. But it has to be catchy, it has to be powerful, or else it would not be able to resonate with everyone, from even the most snobby of hipsters down to the guy who doesn't even really like music all that much and could really do without it. Just take a look here at some rock anthem choruses and see all of the above:

"Come on up for the rising/Come on up, lay your hands in mine/Come on up for the rising/Come on up for the rising tonight."

-Bruce Springsteen

"We can be heroes...just for one day."

-David Bowie

"Na, nah nah, nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah nah, hey Jude!"

-The Beatles

All instantly recognizable, all instantly hummable. If you've heard the song before (I suppose liking it would help some), you can instantly belt out the chorus. They're all anthemic. All epic-sounding, all-relatable, all-inspiring, all-encompassing...that is what a rock anthem is.

-------

Yeah, you can name 'em. Everyone recognizes them. From virtually every song by Bruce Springsteen to David Bowie's "Heroes," from "Hey Jude" by the Beatles (moreso the last mantra section) to "Sweet Virginia" by the Rolling Stones, rock anthems are powerful tools that are amazing because they inspire the listener and create such intense emotions in the listener so much as to create action, usually. Sometimes to even relate in music you need a rock anthem because their "sound," their energy, their spirit is a great unifier of people. This is why when a song like "Bohemian Rhapsody" comes on, everyone, and I mean everyone (unless you are so hipster that you choose to non-conform to such a tradition) goes full throttle into the song all through the end. True rock anthems are, quite simply, uniters and not dividers. So really, what distinguishes the rock anthem and what makes it so good?

The main ingredient in a rock anthem is usually the "sense of the epic." While this sounds broad, nondescript and generally useless, it's the best term to use. What may help illustrate my point, however, are examples of the "sense of the epic." Bruce Springsteen, as mentioned before, is essentially the king of the rock anthem, and one of his most widely known tracks, "Born to Run," illustrates the point. It sounds big. It goes for broke. The power in the song rattles you to your bones. His lyrics also display of a "sense of the epic, " painting desolation around but lo! the eternal ray of light that is worth pursuing prevails! For Bruce Springsteen's characters, it's quite simply a "do or die" moment and this sense of utmost importance and urgency imbues the song with a strong sense of power, direction, and purpose, not to mention an overall "sense of the epic."

Therefore, is there a sound that defines the rock anthem? I'd argue that there isn't, though the evidence seems to suggest the contrary. Tracks like the aforementioned "Heroes" (by Bowie), "Bohemian Rhapsody" or even "Wake Up" by Arcade Fire all have extremely ornate production. The layering of such a large quantity of instruments (an offshoot or spinoff of the "Wall of Sound") generates a large sound, hence the "sense of the epic" and hence a rock anthem. However, I would also posit that anthems such as "Sweet Virginia" by the Rolling Stones, "Hey Jude" by the Beatles, and other tunes like "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" all suggest that the rock anthem as a dense and layered concoction brewed in the studio may not be necessarily true, though the trend is evident and typically suggests otherwise.

For a rock anthem to truly succeed, the necessary portion is that of the chorus. If the chorus is not rally-worthy, then the song is not a rock anthem. It's the power in the chorus that makes the rock anthem such a uniter: who doesn't sing "BORNNNNN IN THE USAAAAAAAA-EAAAAAAA!!!!!!!" when it comes on? I rest my case. The chorus has to be easily accessible: even the layman must be able to get around to remember it, so that perhaps even in his drunkest hour he may be able to belt out the chorus when prompted. But it has to be catchy, it has to be powerful, or else it would not be able to resonate with everyone, from even the most snobby of hipsters down to the guy who doesn't even really like music all that much and could really do without it. Just take a look here at some rock anthem choruses and see all of the above:

"Come on up for the rising/Come on up, lay your hands in mine/Come on up for the rising/Come on up for the rising tonight."

-Bruce Springsteen

"We can be heroes...just for one day."

-David Bowie

"Na, nah nah, nah nah nah nah, nah nah nah nah, hey Jude!"

-The Beatles

All instantly recognizable, all instantly hummable. If you've heard the song before (I suppose liking it would help some), you can instantly belt out the chorus. They're all anthemic. All epic-sounding, all-relatable, all-inspiring, all-encompassing...that is what a rock anthem is.

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

A Short Exercise: Top 25 Records, Ever?

In my very very first entry, I already determined the top five records of all time based on whatever barometers I came up with...and this is what I did come up with:

Do I still agree with these top five? I think so. No record has come out within the last 20 years that could get close. But as an intellectual exercise for myself (and for you to see, I suppose), I present to you what I would consider to be the top twenty records of all time:

1. Bob Dylan - Highway 61 Revisited

2. The Beatles - Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

3. The Band - Music From Big Pink

4. The Clash - London Calling

5. The Beach Boys - Pet Sounds

6. The Velvet Underground - The Velvet Underground & Nico

7. The Beatles - The Beatles

8. John Coltrane - A Love Supreme

9. The Beatles - Revolver

10. Bob Dylan - Blonde on Blonde

11. The Rolling Stones - Exile on Main Street

12. Marvin Gaye - What's Going On

13. The Beatles - Abbey Road

14. The Rolling Stones - Beggar's Banquet

15. Bob Dylan - Bringing It All Back Home

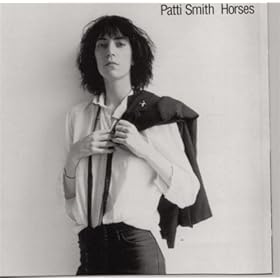

16. Patti Smith - Horses

17. Television - Marquee Moon

18. Joy Division - Unknown Pleasures

19. Sonic Youth - Daydream Nation

20. Bruce Springsteen - Born to Run

21. David Bowie - Low

22. The Velvet Underground - The Velvet Underground

23. Jimi Hendrix - Electric Ladyland

24. Led Zeppelin - Physical Graffiti

25. Bob Dylan Blood on the Tracks

Looking over this list, there could be some changes, i.e. dropping Zeppelin off the list, but overall it provides a solid start, as I never have tried to completely rank 1-25 of the best records ever. The records I'm especially high here that show up in the top 25 whereas they normally wouldn't be are The Velvet Underground, Low, and Physical Graffiti. I perhaps have underrated Revolver, Blood on the Tracks and Marquee Moon, but I am rather satisfied with the list at the moment. Do note with some hilarity that no record released after 1988 made this list (and if you discount Daydream Nation, no record was released after the 1970s...). I think it quite clearly indicates a trend that "old school" is "good school"...if I were to use the vernacular.

Next up will likely be looking at culture appropriation in rock music. That is likely to say, the entire history of rock music, since much of it has just been stealing culture unique to sections of society and incorporating it into the general framework of rock music.

1. Highway 61 Revisited

2. Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

3. Music From Big Pink

4. London Calling

5. Pet SoundsDo I still agree with these top five? I think so. No record has come out within the last 20 years that could get close. But as an intellectual exercise for myself (and for you to see, I suppose), I present to you what I would consider to be the top twenty records of all time:

1. Bob Dylan - Highway 61 Revisited

2. The Beatles - Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

3. The Band - Music From Big Pink

4. The Clash - London Calling

5. The Beach Boys - Pet Sounds

6. The Velvet Underground - The Velvet Underground & Nico

7. The Beatles - The Beatles

8. John Coltrane - A Love Supreme

9. The Beatles - Revolver

10. Bob Dylan - Blonde on Blonde

11. The Rolling Stones - Exile on Main Street

12. Marvin Gaye - What's Going On

13. The Beatles - Abbey Road

14. The Rolling Stones - Beggar's Banquet

15. Bob Dylan - Bringing It All Back Home

16. Patti Smith - Horses

17. Television - Marquee Moon

18. Joy Division - Unknown Pleasures

19. Sonic Youth - Daydream Nation

20. Bruce Springsteen - Born to Run

21. David Bowie - Low

22. The Velvet Underground - The Velvet Underground

23. Jimi Hendrix - Electric Ladyland

24. Led Zeppelin - Physical Graffiti

25. Bob Dylan Blood on the Tracks

Looking over this list, there could be some changes, i.e. dropping Zeppelin off the list, but overall it provides a solid start, as I never have tried to completely rank 1-25 of the best records ever. The records I'm especially high here that show up in the top 25 whereas they normally wouldn't be are The Velvet Underground, Low, and Physical Graffiti. I perhaps have underrated Revolver, Blood on the Tracks and Marquee Moon, but I am rather satisfied with the list at the moment. Do note with some hilarity that no record released after 1988 made this list (and if you discount Daydream Nation, no record was released after the 1970s...). I think it quite clearly indicates a trend that "old school" is "good school"...if I were to use the vernacular.

Next up will likely be looking at culture appropriation in rock music. That is likely to say, the entire history of rock music, since much of it has just been stealing culture unique to sections of society and incorporating it into the general framework of rock music.

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

Rapid Reaction: Patti Smith - Horses

I suppose the good question is this: how did it take me so long to get to this record? And my answer is this: I sincerely don't know. It's got all the connections that would put it on my radar: John Cale produced this, it counts as proto-punk, Tom Verlaine played on the record and you can connect Van Morrison and the Smiths to this. I realize that my position pretty indefensible...there is no real excuse for not hearing this until now, but at least I've now rectified that mistake.

I've listened to it once and am currently working through it the second time as I write this, and I can honestly say it deserves all the cred it gets: it's a masterwork. It's one of those records that will blow your mind open; it blasts your brains, picks up the pieces and reforms your brain into something new. All from the first note.

Aside from the intro to "Gloria" that slinks in before it makes its presence known, the record is a ball of fury and energy, and if you're not getting blitzed by the energy in the proto-punk sound, you're getting blitzed by her lyrics, which are part beat poetry and part stream-of-consciousness not unlike the master himself, Bob Dylan. The sound has a proto-punk roar that hangs around the big guys like the Velvet Underground, and Patti Smith sounds like an extremely angry cross between Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. The passion in this record doesn't just seep out and let you "sort of" feel it: the amount of passion in this record is explosion-inducing and you feel it. And if you don't, you're not alive. Plain and simple.

I don't know how else to put it. This record is a force of nature. And it's one to behold. I'm sure a lot of others have been able to wax more poetic about it than I have, but maybe that would do the record an injustice, as it's so stripped down and bare in its proto-punk approach, that to speak more about is contrary to the spirit of the record. It's one that has to be heard to be believed.

Friday, October 15, 2010

Spirituality and Music, redux

Two entries in two days?!? I am finally starting to get back into the swing of things, apparently. Homework beckons, but my thoughts beckon more...

---------------------

You can search for my old entry (about a year old) and see that I railed quite heavily on the genre of Christian rock music for its faults. It was because quite frankly, it is still true to a great extent. I still find Christian rock to be rather pedestrian and unimaginative, but as I've recently been trying to live out the penultimate words of George Harrison ("Everything can wait, but the search for God cannot wait."), I perhaps may have judged the genre too harshly. It is worship music, and despite my perception of it, people still connect to it and through it to that higher plane, so it must therefore hold some value. And as everyone knows, music is one of the most subjective fields, so when it comes to trying to organize it and present it in a remotely academic manner there is bound to be some oversight, and I am "being the bigger man" in admitting to some of that.

But that does not mean that I am totally recanting my statement. It just means that I previously undervalued it. What made me reconsider my stance was something the legendary Mavis Staples said when interviewed on the Colbert Report. When asked about her reasons for moving from gospel to soul in the 1960s (and her thoughts about the cries of "traitor" it generated from the community), Mavis essentially said: "All music glorifies God." While I'm unsure if she is familiar with Slayer, one realizes it is essentially true. And it simply goes beyond any religious notions. Whether or not one believes in the vehicle of God or otherwise, music is inherently powerful and it showcases the unique power that humanity has, in weakness and in strength. Whether it is worship music or gleefully skewering religion (see: "Highway 61 Revisited" for a particularly delightful roasting of the Abraham story), it all essentially carries infinite power and meaning. That is what makes music, well, music.

I still think that Christian rock has quite a-ways to go if it wants to be considered as proficient in the "academic" and "quality" sense I have been trying to impart. If I may continue tooting this particular horn, it is so pre-occupied with presenting the message of Lord without realizing that the music itself is already the message! Music already glorifies the Lord, so if you simply strive make good music, you are already completing your objective! Now, this is not obvious to most people, so I understand that perhaps in needing to spread their message they are tempted to brandish a big stick, but that is what makes the music so pedestrian to me. The music becomes clumsy and unimaginative when the only thing music has is to be graceful and imaginative! I don't necessarily mean this in the technical-playing sense (thus punk would be ruled out, and we all know punk has too much heart and balls of steel for that), but in the artistic, striving-for-quality sense. As evidence, I present the best "worship" record of all time, in my opinion:

A Love Supreme is beyond a masterwork: it is a monolith of the power of music, standing tall as a man among boys. Far and away the best jazz record of all time (it would most certainly rank in my top 20, if not top 10 records of all time), it is a testament: to Coltrane's power, to Coltrane's skill, to Coltrane's faith. Coltrane made the record to demonstrate his faith and his love for his Lord. The devotional poem in the liner notes is "recited" via his saxophone in the last movement, with the final lines in that poem showing his love for God:

"Elation. Elegance. Exaltation. All from God. Thank you God. Amen."

The record is overbearing only in that it is overbearingly perfect. It does not wield its faith like a stick to beat home the point, but the faith is implemented like a fine knife used to carve the most detailed of sculptures. The search for quality in the music mirrors Coltrane's search for God, and in both Coltrane finds what he had been looking for. It doesn't matter if you aren't a believer or not in Coltrane's faith. The music contains so much of that often-sought "soul" that by the end of the record you believe: if not in his faith or his skill, you will at least believe in the power of music.

And it reinforces the point I have been trying to hit home in this entry: the power of music is the power of that higher plane. Take care of the first and the rest will follow. It is something that Christian rock would do well to heed if it wants to reinforce its connection to the Lord and actually serve as quality music. Under the "Mavis Staples assumption" (as I'll call it from here on out...assuming I ever refer back to it), any music is inherently worship music, so quality music is the highest worship music attainable. So strive for it. Music is a microcosm of life: if one stops searching for meaning and quality, then all is hopeless and futile.

-----------------------

If one needs proof that Christian rock needs to strive for quality once more, one only needs to realize that it was skewered rather successfully by South Park in the Season 7 episode "Christian Rock Hard."

---------------------

You can search for my old entry (about a year old) and see that I railed quite heavily on the genre of Christian rock music for its faults. It was because quite frankly, it is still true to a great extent. I still find Christian rock to be rather pedestrian and unimaginative, but as I've recently been trying to live out the penultimate words of George Harrison ("Everything can wait, but the search for God cannot wait."), I perhaps may have judged the genre too harshly. It is worship music, and despite my perception of it, people still connect to it and through it to that higher plane, so it must therefore hold some value. And as everyone knows, music is one of the most subjective fields, so when it comes to trying to organize it and present it in a remotely academic manner there is bound to be some oversight, and I am "being the bigger man" in admitting to some of that.

But that does not mean that I am totally recanting my statement. It just means that I previously undervalued it. What made me reconsider my stance was something the legendary Mavis Staples said when interviewed on the Colbert Report. When asked about her reasons for moving from gospel to soul in the 1960s (and her thoughts about the cries of "traitor" it generated from the community), Mavis essentially said: "All music glorifies God." While I'm unsure if she is familiar with Slayer, one realizes it is essentially true. And it simply goes beyond any religious notions. Whether or not one believes in the vehicle of God or otherwise, music is inherently powerful and it showcases the unique power that humanity has, in weakness and in strength. Whether it is worship music or gleefully skewering religion (see: "Highway 61 Revisited" for a particularly delightful roasting of the Abraham story), it all essentially carries infinite power and meaning. That is what makes music, well, music.

I still think that Christian rock has quite a-ways to go if it wants to be considered as proficient in the "academic" and "quality" sense I have been trying to impart. If I may continue tooting this particular horn, it is so pre-occupied with presenting the message of Lord without realizing that the music itself is already the message! Music already glorifies the Lord, so if you simply strive make good music, you are already completing your objective! Now, this is not obvious to most people, so I understand that perhaps in needing to spread their message they are tempted to brandish a big stick, but that is what makes the music so pedestrian to me. The music becomes clumsy and unimaginative when the only thing music has is to be graceful and imaginative! I don't necessarily mean this in the technical-playing sense (thus punk would be ruled out, and we all know punk has too much heart and balls of steel for that), but in the artistic, striving-for-quality sense. As evidence, I present the best "worship" record of all time, in my opinion:

A Love Supreme is beyond a masterwork: it is a monolith of the power of music, standing tall as a man among boys. Far and away the best jazz record of all time (it would most certainly rank in my top 20, if not top 10 records of all time), it is a testament: to Coltrane's power, to Coltrane's skill, to Coltrane's faith. Coltrane made the record to demonstrate his faith and his love for his Lord. The devotional poem in the liner notes is "recited" via his saxophone in the last movement, with the final lines in that poem showing his love for God:

"Elation. Elegance. Exaltation. All from God. Thank you God. Amen."

The record is overbearing only in that it is overbearingly perfect. It does not wield its faith like a stick to beat home the point, but the faith is implemented like a fine knife used to carve the most detailed of sculptures. The search for quality in the music mirrors Coltrane's search for God, and in both Coltrane finds what he had been looking for. It doesn't matter if you aren't a believer or not in Coltrane's faith. The music contains so much of that often-sought "soul" that by the end of the record you believe: if not in his faith or his skill, you will at least believe in the power of music.

And it reinforces the point I have been trying to hit home in this entry: the power of music is the power of that higher plane. Take care of the first and the rest will follow. It is something that Christian rock would do well to heed if it wants to reinforce its connection to the Lord and actually serve as quality music. Under the "Mavis Staples assumption" (as I'll call it from here on out...assuming I ever refer back to it), any music is inherently worship music, so quality music is the highest worship music attainable. So strive for it. Music is a microcosm of life: if one stops searching for meaning and quality, then all is hopeless and futile.

-----------------------

If one needs proof that Christian rock needs to strive for quality once more, one only needs to realize that it was skewered rather successfully by South Park in the Season 7 episode "Christian Rock Hard."

Thursday, October 14, 2010

What's (Not) Wrong With Electronica

Once again, supremely late, but once again I find myself unwilling to commit myself to sleeping (despite a severe lack of it) and so I finally now have the time to commit some of my thoughts once again...

-----------------

Yes, I've always considered older music to be infinitely better than what's out now. You get a true sense of soul from it, from Sam Cooke (i.e. Live at the Harlem Square Club 1963) to the wistful sighs of Richard Manuel and the way he, Rick Danko, and Levon Helm combine to tug at your heartstrings, there is always the sense of "soul" found in the recording. It speaks, it breathes character, exudes emotions. Those feelings are what let us connect to the music, and at least for me I find that older music fosters that in a much more meaningful way (let alone connect at all). Modern music just always seemed to lack that "soul" that would draw me to it. Until, perhaps, now.

Perhaps I had judged it incorrectly. Electronica/dance is a different beast compared to rock and roll (though it can certainly be an analogous construct): it must be evaluated on separate parameters. It's unlikely that electronica/dance will provide the payoff that, say, a Staple Singers track may provide with goosebump-causing moments, where Mavis and co. just pull off that moment of release with utmost mastery. However, electronica/dance still can contain soul, but it's not in the same way rock and roll often stakes its livelihoods in those climaxes (ahem...Sigur Rós). Electronica/dance contains "soul" once it establishes a beat: but it has to grab you from your "inner core," so to speak, and drive you to simply feel it. A true track would likely simply cause you to want, or even need, to dance.

Case in point? Daft Punk. They can be classified as French house, which is apparently separate from Detroit house, from all other sorts of electronica, but at least when it comes to mainstream/crossover appeal, no one has had more success than Daft Punk. And it's not especially difficult to see how and why.

Perhaps moreover known for being sampled by le Kanye West in his track "Stronger," it is impossible to deny that Daft Punk craft excellent tracks. From "Da Funk" to "Around the World," "Face to Face," "One More Time," and "Robot Rock," Daft Punk essentially have mastered their form of art. Their beats are uncomplicated, and perhaps therein lies the charm. They utilize basic beats but the layers above add the character to the track, allowing for someone to simply be "grabbed" and pulled into the song (and, perhaps, into dancing). Oftentimes, unlike other artists, they tend to emphasize the groove and tend to delve into "funk"-ier areas of existence, such as "Da Funk," which is essentially a clinic on how to groove like a master.

But it's really their live material where they shine. On Alive 1997, they essentially DJ for 45 straight minutes, rolling through such prime cuts like "Rollin' and Scratchin'," the oft-mentioned "Da Funk," among other tracks. The tracks are stretched, altered, and fixed up to match the length, with interludes and other bits providing perfect segues in between the more recognizable sections. Then, on Alive 2007, Daft Punk essentially provide a "Greatest Hits" DJ-mashup attack, smartly and cleverly combining tracks to provide new glances at them and give them a fresh context and meaning. "Television Rules the Nation" kicks off one track, and when combined with "Crescendolls" off of Discovery, gives both tracks strange new life as the tone of "Crescendolls" gets dramatically altered with "Television Rules the Nation" thumping under it. "Face to Face" is also a prime example of such as the disco feel in the backbeat is replaced by the "Harder Better Faster Stronger" theme, giving the song a fresh backdrop and also a subliminal meaning that gels quite nicely with the intent of "Face to Face" before it segues into "Short Circuit."

While I certainly love Discovery, Homework, and Human After All to death, it is impossible to say that Daft Punk aren't a better live machine than a studio machine. And that is saying quite a lot given that Discovery is at least a "masterwork +," Homework is a "masterwork" and Human After All is "reasonably good" (tracks off of Human After All benefit considerably on Alive 2007 with the mashups providing new context and life).

Regardless, after waxing at length about the prowess of Daft Punk, the point is this: after listening to them for awhile and finally getting into it, their records made me realize that perhaps electronica/dance could perhaps contain what I have always sought in music, that being "soul." It's not the same sort of "soul" as I had been searching for prior, and that is the likely reason why I hadn't found it; I simply wasn't looking in the right place for the "soul" of the work. Amidst all the rigidity in structure, form, and instrumentation, the "soul" was indeed possible in the energy of the work, that it infiltrates you and makes you unable of doing anything else but enjoying the work present.

I am no electronica/dance expert, but the existence of Daft Punk disproved my "technological advancement is bad for music" theory. I had figured it was a sure way to wipe the soul straight out of a work, but I was apparently wrong, as a compelling counter-argument has revealed itself. Daft Punk could perhaps be a rare exception to the rule, but an exception's existence makes the theory likely wrong. Further examination will likely have to follow. But that still doesn't mean that I prefer modern music to old-school music, it just means that I undervalued it.

PS. I have an odd question: is there EVER an inappropriate time to listen to Daft Punk? I thought so.

-----------------

Yes, I've always considered older music to be infinitely better than what's out now. You get a true sense of soul from it, from Sam Cooke (i.e. Live at the Harlem Square Club 1963) to the wistful sighs of Richard Manuel and the way he, Rick Danko, and Levon Helm combine to tug at your heartstrings, there is always the sense of "soul" found in the recording. It speaks, it breathes character, exudes emotions. Those feelings are what let us connect to the music, and at least for me I find that older music fosters that in a much more meaningful way (let alone connect at all). Modern music just always seemed to lack that "soul" that would draw me to it. Until, perhaps, now.

Perhaps I had judged it incorrectly. Electronica/dance is a different beast compared to rock and roll (though it can certainly be an analogous construct): it must be evaluated on separate parameters. It's unlikely that electronica/dance will provide the payoff that, say, a Staple Singers track may provide with goosebump-causing moments, where Mavis and co. just pull off that moment of release with utmost mastery. However, electronica/dance still can contain soul, but it's not in the same way rock and roll often stakes its livelihoods in those climaxes (ahem...Sigur Rós). Electronica/dance contains "soul" once it establishes a beat: but it has to grab you from your "inner core," so to speak, and drive you to simply feel it. A true track would likely simply cause you to want, or even need, to dance.

Case in point? Daft Punk. They can be classified as French house, which is apparently separate from Detroit house, from all other sorts of electronica, but at least when it comes to mainstream/crossover appeal, no one has had more success than Daft Punk. And it's not especially difficult to see how and why.

Perhaps moreover known for being sampled by le Kanye West in his track "Stronger," it is impossible to deny that Daft Punk craft excellent tracks. From "Da Funk" to "Around the World," "Face to Face," "One More Time," and "Robot Rock," Daft Punk essentially have mastered their form of art. Their beats are uncomplicated, and perhaps therein lies the charm. They utilize basic beats but the layers above add the character to the track, allowing for someone to simply be "grabbed" and pulled into the song (and, perhaps, into dancing). Oftentimes, unlike other artists, they tend to emphasize the groove and tend to delve into "funk"-ier areas of existence, such as "Da Funk," which is essentially a clinic on how to groove like a master.

But it's really their live material where they shine. On Alive 1997, they essentially DJ for 45 straight minutes, rolling through such prime cuts like "Rollin' and Scratchin'," the oft-mentioned "Da Funk," among other tracks. The tracks are stretched, altered, and fixed up to match the length, with interludes and other bits providing perfect segues in between the more recognizable sections. Then, on Alive 2007, Daft Punk essentially provide a "Greatest Hits" DJ-mashup attack, smartly and cleverly combining tracks to provide new glances at them and give them a fresh context and meaning. "Television Rules the Nation" kicks off one track, and when combined with "Crescendolls" off of Discovery, gives both tracks strange new life as the tone of "Crescendolls" gets dramatically altered with "Television Rules the Nation" thumping under it. "Face to Face" is also a prime example of such as the disco feel in the backbeat is replaced by the "Harder Better Faster Stronger" theme, giving the song a fresh backdrop and also a subliminal meaning that gels quite nicely with the intent of "Face to Face" before it segues into "Short Circuit."

While I certainly love Discovery, Homework, and Human After All to death, it is impossible to say that Daft Punk aren't a better live machine than a studio machine. And that is saying quite a lot given that Discovery is at least a "masterwork +," Homework is a "masterwork" and Human After All is "reasonably good" (tracks off of Human After All benefit considerably on Alive 2007 with the mashups providing new context and life).

Regardless, after waxing at length about the prowess of Daft Punk, the point is this: after listening to them for awhile and finally getting into it, their records made me realize that perhaps electronica/dance could perhaps contain what I have always sought in music, that being "soul." It's not the same sort of "soul" as I had been searching for prior, and that is the likely reason why I hadn't found it; I simply wasn't looking in the right place for the "soul" of the work. Amidst all the rigidity in structure, form, and instrumentation, the "soul" was indeed possible in the energy of the work, that it infiltrates you and makes you unable of doing anything else but enjoying the work present.

I am no electronica/dance expert, but the existence of Daft Punk disproved my "technological advancement is bad for music" theory. I had figured it was a sure way to wipe the soul straight out of a work, but I was apparently wrong, as a compelling counter-argument has revealed itself. Daft Punk could perhaps be a rare exception to the rule, but an exception's existence makes the theory likely wrong. Further examination will likely have to follow. But that still doesn't mean that I prefer modern music to old-school music, it just means that I undervalued it.

PS. I have an odd question: is there EVER an inappropriate time to listen to Daft Punk? I thought so.

Thursday, September 9, 2010

The Art of the Pastiche

Tremendous oversight, perhaps, or just post-(re-)moving, I have neglected this vehicle of thought for far too long, probably. But here I am, again, and now I am ready to hit the road again (as far as writing on here is concerned). I've actually been meaning to write this entry for awhile now (a very long while, come to think of it), so here it finally is.

----

All music is derived. Yes, it's true. No artist is completely original. Not even the Beatles. Shocking? Perhaps to some, but it's the truth. Most artists try to brand themselves as entirely unique: after all, if you're the first one there, you're at least going to get the title of "progenitor of ______ genre," if not "Godfather and King of _______ genre."

But what of the musical pastiche? Surely no one would ever consider engaging themselves in the art of the pastiche if it got one nowhere. Utterly useless. However, music is luckily one of those things where as long as it's good, it's good.

I suppose I should clarify as to what a musical pastiche is. A pastiche is basically an artistic work which borrows heavily from themes present in earlier works. So a musical pastiche is simply some work (song, obviously in the context here) that borrows heavily from other themes.

How does one make a pastiche not come across as a trite, meaningless wankery? Well, the obvious key is that it simply has to be a good song. While not very helpful in the sense of getting to the heart of a good pastiche, it's true. It has to be a good song more than anything else. However, a few identifying characteristics:

1. As a musical pastiche, you can borrow heavily from a certain style or genre, but please, never make it a complete ripoff. Not only would you get your bum sued in a second (lawyers are prone to do that these days) but you'd also be derided in critical circles as nothing but a copycat...which may or may not be true given the circumstances.

2. The song should attempt to align with the genre's characteristics as much as possible. While this sounds exactly like the first point, it actually travels a lot deeper than that. Say you're doing a music hall pastiche (will come back to this later, too...). Do you write lyrics that would befit a Joy Division song? No sir, music hall is lighthearted. Singing about how the world is a heartless place like that would do no good for your song. Do you make your song sound like music hall? Of course, or else it wouldn't be called a pastiche of music hall. It would be just some derivation of music hall, and who knows...you could be credited with a sub-genre if you do so. But that's not the point.

3. The pastiche is usually outside of the grasp of the artist's usual work, but by no means should the genre pastiched be too far out of the ordinary. This means someone, like Arcade Fire, for example, cannot dabble into rap-rock and get away with calling it a pastiche.

4. Every pastiche is essentially a tribute to the source material, and should thus do it proud in some way.

There are few rules to the art of pastiche, but it's incredibly hard to pull off without coming across as meaningful and honest. A couple that come to mind are explained below:

The Beatles is chock full of pastiches, but McCartney is probably the most willing (or perhaps guilty, depending on your attitude towards the man) when it comes to pastiches. "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da" was a sendup of reggae, while "Martha My Dear" and "Honey Pie" were the sendups of music hall (see? It returns). "Honey Pie" is perhaps the best example. Stealing everything from lyrical plot to soundscape, it is unmistakably music hall. Yet, it is a whimsical tune that stands well and still sounds unmistakably like a Beatles song. While perhaps sticking out like a sore thumb on other records (other Beatles records, even), it integrates remarkably well into the record (perhaps because the album itself is essentially many different pastiches, it blends into the woodwork, being one itself).

A more modern example of effective pastiches:

James Murphy has been sticking pastiches on most of his LCD Soundsystem records. "Never As Tired As When I'm Waking Up" was a straight send-up of the Beatles in their the Beatles era, drawing heavily from tunes like "Dear Prudence" and "While My Guitar Gently Weeps." However, James Murphy as LCD Soundsystem never pastiche-d as boldly as they did on This Is Happening.

"Drunk Girls" is as it sounds: a song about drunk girls. Musically, it's almost indistinguishable from the Velvet Underground's "White Light/White Heat." Spiritually, they're the same: the omnipresent theme of self-discovery and self-fulfillment, one via drugs and one via getting it on. Out of the two major pastiches on the record, this is perhaps one the more "shameless" pastiches of the three on the record (the third, not discussed here, is "Somebody's Calling Me," a song that essentially cops Iggy Pop's magnificent "Nightclubbing"), but the song is too raucous and joyful to submit to cheapness.

"All I Want" is the true pastiche on the record. If you've listened to David Bowie's track "Heroes," you know it's probably one of the greatest songs, ever. "All I Want" is Murphy's attempt at distilling what makes "Heroes" so damn good and make it his own...and Murphy does find success. It's a somber affair overall in "All I Want," but the feeling of catharsis that is somehow pulled off makes the song one of the most affecting in LCD Soundsystem's catalog, and is what allows "All I Want" to even hold a candle to "Heroes."

With such blatant callbacks to particular songs on the record, James Murphy certainly put those songs in danger of being completely meaningless and underwhelming. Perhaps it's a testament to his skills as an artist and songwriter that he managed to avoid frivolity from happening at large.

----

All music is derived. Yes, it's true. No artist is completely original. Not even the Beatles. Shocking? Perhaps to some, but it's the truth. Most artists try to brand themselves as entirely unique: after all, if you're the first one there, you're at least going to get the title of "progenitor of ______ genre," if not "Godfather and King of _______ genre."

But what of the musical pastiche? Surely no one would ever consider engaging themselves in the art of the pastiche if it got one nowhere. Utterly useless. However, music is luckily one of those things where as long as it's good, it's good.

I suppose I should clarify as to what a musical pastiche is. A pastiche is basically an artistic work which borrows heavily from themes present in earlier works. So a musical pastiche is simply some work (song, obviously in the context here) that borrows heavily from other themes.

How does one make a pastiche not come across as a trite, meaningless wankery? Well, the obvious key is that it simply has to be a good song. While not very helpful in the sense of getting to the heart of a good pastiche, it's true. It has to be a good song more than anything else. However, a few identifying characteristics:

1. As a musical pastiche, you can borrow heavily from a certain style or genre, but please, never make it a complete ripoff. Not only would you get your bum sued in a second (lawyers are prone to do that these days) but you'd also be derided in critical circles as nothing but a copycat...which may or may not be true given the circumstances.

2. The song should attempt to align with the genre's characteristics as much as possible. While this sounds exactly like the first point, it actually travels a lot deeper than that. Say you're doing a music hall pastiche (will come back to this later, too...). Do you write lyrics that would befit a Joy Division song? No sir, music hall is lighthearted. Singing about how the world is a heartless place like that would do no good for your song. Do you make your song sound like music hall? Of course, or else it wouldn't be called a pastiche of music hall. It would be just some derivation of music hall, and who knows...you could be credited with a sub-genre if you do so. But that's not the point.

3. The pastiche is usually outside of the grasp of the artist's usual work, but by no means should the genre pastiched be too far out of the ordinary. This means someone, like Arcade Fire, for example, cannot dabble into rap-rock and get away with calling it a pastiche.

4. Every pastiche is essentially a tribute to the source material, and should thus do it proud in some way.

There are few rules to the art of pastiche, but it's incredibly hard to pull off without coming across as meaningful and honest. A couple that come to mind are explained below:

The Beatles is chock full of pastiches, but McCartney is probably the most willing (or perhaps guilty, depending on your attitude towards the man) when it comes to pastiches. "Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da" was a sendup of reggae, while "Martha My Dear" and "Honey Pie" were the sendups of music hall (see? It returns). "Honey Pie" is perhaps the best example. Stealing everything from lyrical plot to soundscape, it is unmistakably music hall. Yet, it is a whimsical tune that stands well and still sounds unmistakably like a Beatles song. While perhaps sticking out like a sore thumb on other records (other Beatles records, even), it integrates remarkably well into the record (perhaps because the album itself is essentially many different pastiches, it blends into the woodwork, being one itself).

A more modern example of effective pastiches:

James Murphy has been sticking pastiches on most of his LCD Soundsystem records. "Never As Tired As When I'm Waking Up" was a straight send-up of the Beatles in their the Beatles era, drawing heavily from tunes like "Dear Prudence" and "While My Guitar Gently Weeps." However, James Murphy as LCD Soundsystem never pastiche-d as boldly as they did on This Is Happening.

"Drunk Girls" is as it sounds: a song about drunk girls. Musically, it's almost indistinguishable from the Velvet Underground's "White Light/White Heat." Spiritually, they're the same: the omnipresent theme of self-discovery and self-fulfillment, one via drugs and one via getting it on. Out of the two major pastiches on the record, this is perhaps one the more "shameless" pastiches of the three on the record (the third, not discussed here, is "Somebody's Calling Me," a song that essentially cops Iggy Pop's magnificent "Nightclubbing"), but the song is too raucous and joyful to submit to cheapness.

"All I Want" is the true pastiche on the record. If you've listened to David Bowie's track "Heroes," you know it's probably one of the greatest songs, ever. "All I Want" is Murphy's attempt at distilling what makes "Heroes" so damn good and make it his own...and Murphy does find success. It's a somber affair overall in "All I Want," but the feeling of catharsis that is somehow pulled off makes the song one of the most affecting in LCD Soundsystem's catalog, and is what allows "All I Want" to even hold a candle to "Heroes."

With such blatant callbacks to particular songs on the record, James Murphy certainly put those songs in danger of being completely meaningless and underwhelming. Perhaps it's a testament to his skills as an artist and songwriter that he managed to avoid frivolity from happening at large.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)