There are certain figures regarded as immortal in rock music. To name a few:

Jimi Hendrix

Jim Morrison

John Lennon

Bob Marley

Ray Charles

Marvin Gaye

George Harrison

Kurt Cobain

Joe Strummer

Johnny Cash

Stevie Ray Vaughn

John Bonham

Elliot Smith

Keith Moon

and the like. I don't necessarily agree with some inclusions (I'm not sold on Morrison and Cobain, for starters), but for all intents and purposes those are commonly known "immortals" in rock music. What holds these together? They're all dead. And this leads me to my first Immutable Law in Rock Music:

"

To be truly immortal in Rock Music, one must die.

"

Of course, this makes zero sense at first. If you're dead, how are you alive? You're no longer making music. But take a look. Posthumous careers for many of these careers have either overshadowed or recharged some careers. I'm going to pull a different example than some of the people I listed above to prove my point: Ian Curtis of Joy Division.

Joy Division were not really well known when Curtis died. They were on the rise, but not really at that point yet where they got it "good." And then, poof! Ian Curtis, gone from the world. And then everyone discovered "Love Will Tear Us Apart," and the landmark records Unknown Pleasures and Closer. Then, all of a sudden, Joy Division were kind of a big deal. This allowed New Order (the rest of Joy Division) to get a head start, and has furthermore led to reissues, reprintings, and box sets of Joy Division's work. If Ian Curtis had died, would Joy Division have been big? Sure. Would they have been as big as they are now had Ian Curtis died? Arguably, no. Ian Curtis' death casts a long shadow over the melancholia that permeates every Joy Division song. In light of his depression and epilepsy, Joy Division records and songs gain a whole backstory and a whole new meaning. Divorced from their meaning, the songs are quite obviously powerful, muscular, and constantly effecting, but with this meaning every Joy Division song becomes a tour de force that simply obliterates the listener when heard.

The context of death makes everything about the artist more striking, granting the band/artist an aura that is impossible to penetrate. To elaborate on the above example, Ian Curtis, on his dying day, watched a Herzog film, put on Iggy Pop's the Idiot, and then hung himself. Curtis has attained a sort of mysticism due to that. Marvin Gaye was shot by his father, John Lennon was assassinated, while Kurt Cobain and Jimi Hendrix died due to overdoses. They're all now seen with a sort of reverence, an air of the mystic thanks to their deaths.

Each person who has died in the midst of their career has, in a sense, gained a sort of "impenetrable fog" that protects them from any sort of heated criticism and guarantees them a favorable standing in the world of rock music. I'm not saying it's undeserved. Lennon obviously deserves the "impenetrable fog"; his work with the Beatles, Plastic Ono Band and Imagine are all stone-cold classics and monoliths in rock music, and as an activist his edge has been unmatched. But Walls and Bridges? Some Time In New York City? Neither record is much better than mediocre, in my humble opinion. But his death erased any sort of criticism that could be levied against him.

This is why I'm inclined to believe Paul McCartney often suffers in critic circles: he's still around, he's still pounding it out, but either because he's been oft considered as the "soft" Beatle or because of his long career which has led to a fair number of duds to go alongside his many, many studs, he's likely the least respected Beatle (though perhaps Ringo also is given this same title). Now of course, saying someone is the least-respected Beatle is saying the fourth-most respected artist of all time, but that's neither here nor there. John Lennon has two (to three, depending on your level of scathing) duds to go alongside his studs. Granted, it's folly to extrapolate a career and look at sample sizes to examine careers of rock musicians, but it should be duly noted.

I'm also not ragging against John Lennon. Let me make that clear. John Lennon is the fucking man. I observe his birthday and his dying day every year. I don't take the day off, but for that whole day, John Lennon, everything he did and everything he stood for is always on my mind. But his death has granted him a place in the hallowed hall of rock immortals, perhaps given a slightly easier screening process than others. As have countless others, for better or for worse.

If you look at the ripples caused by a musician's death, the effect is pretty obvious. At least nowadays, the artist in question is rewarded with many, many posthumous awards and accolades. George Harrison was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame shortly after his death. Ray Charles won a whopping eight Grammies from his record, Genius Loves Company, which was released two months after his death. Johnny Cash's American IV won a few CMA's and his rendition of "Hurt" absolutely slayed everyone and reaped some rewards soon after he passed (myself included...but his rendition of "Hurt" is great regardless of the circumstances).

The general rule? In rock music, sometimes it's better to die than to live. It doesn't make any sense, really, but it's true. It's truly a peculiar phenomenon. But it's observable. To refuse to acknowledge its existence is shortsighted. It's not talked about a lot...but it's there. Sort of like a dirty little secret. It's also something that should never be wished on someone. Death for the profit of afterlife. Perhaps it is the manifestation of "what could have been?" had they continued to be around; continued to be the great musicians they were.

Key, though, is to enjoy the careers that these immortals have brought us before their dying breath. In this sense, each album is worth more because there are less albums around. So it's therefore to critical to enjoy each landmark work each immortal brings us, to listen and bask in its eternal glory.

Monday, December 21, 2009

Sunday, December 20, 2009

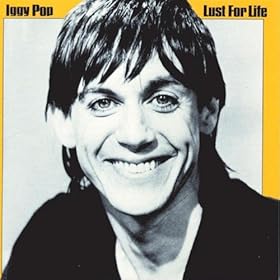

Record of the Moment: Iggy Pop - Lust for Life

Somehow, it is hard to imagine that the cheeky young fellow who appears on this record cover to be the same gaunt-faced man who gave the death stare on the cover of Raw Power. It doesn't seem to add up. Here, the dude is happy. Look at that smile. The man on the cover of Raw Power looks like he wants to tear your throat out and eat it in front of your children. And just look at the title of each record: Lust for Life against Raw Power. One implies positivity, the other implies negativity.

But that's where Iggy Pop ended up. After the royal collapse of the Stooges, and a stint in the hospital, Iggy Pop was back in business. He'd cleaned up, essentially (though this probably isn't totally true). But the glaring difference between the cover of the last Stooges and the cover for this record sort of perpetuates that myth. And in some sense, the music is a little lighter. By no means does this mean Iggy Pop went "lite" on the populace. Nope. I don't think Iggy Pop would be caught dead going "lite," because that is simply the way Iggy Pop is.

Compared to the Idiot, the previous release, Lust for Life is a return to form for Iggy Pop. Personally, in my historical pursuits as a rock scholar, I consider the Idiot to be a sort of half-Bowie, half-Pop record. It's obviously still Iggy. But the music is obviously a predecessor to Bowie's groundbreaker, Low. Therefore, the Idiot is sort of the lost brother to Bowie's trilogy (I'd argue that the Idiot should be included in the "trilogy"; thus expanding the concept into a "quadrilogy"). Some people disown the Idiot for its Bowie-ness. I refuse to do so, personally. Regardless, Lust for Life showed that Pop still not only had his own lyrical edge, but his edge as a musician.

The drums that kick off the record instantly blow open your mind. It's big, it's huge, and instantly memorable (and apparently easily sullied and stained: I'm looking at you, Jet). And then it kicks into gear. The younger and angrier Iggy Pop is largely missing; here instead is an older, wiser Iggy Pop, who knows better now that he's escaped his vices. But of course, he still acknowledges their existence (see: "Some Weird Sin"), because who couldn't? Your vices haunt you forever. Iggy captures it perfectly; after all, of all the people who are familiar with self-destruction, Iggy Pop pretty much tops the list.

But this Iggy Pop is largely over that hill and out of that Hell, and he knows it. The way "Success" gleefully careens along, almost teetering on the edge of collapse but always steady...it's infectious. "The Passenger" is similarly enchanting, but not because it's necessarily a "happy" track; it's an Iggy Pop seemingly at peace. The barroom rock of "Turn Blue" is indicative of Iggy's still-present edge, both morbid and scathing in its attacks, but almost sarcastic in its musings. The track is a reference to Iggy Pop's previous struggles with drugs, as easily discerned, but for all anyone knows the implications are much wider.

While the music itself is nowhere near as ear-bleed-inducing as Raw Power is (which was intentional), that is not to say that Lust for Life is toothless. Tracks such as "Neighborhood Threat" prowl along menacingly, with Iggy Pop's voice of "doom," so to speak, going from its tremble-causing baritone to shattering screams and yelps in a heartbeat...all constantly affecting, if sometimes slightly grating (or very grating, depending on your disposition towards the singing abilities of Iggy Pop). The funk-tinged (most Bowie-like) romp, "Fall in Love with Me" stomps along in a marvelous fashion, with Iggy half-crooning the title line over a contagious groove that is hard to deny.

I could speak at length about every track, but I will stop here. Needless to say, Lust for Life is essential. Standing alone, the record is perfect. Its influence is widespread. Lust for Life is a perfect example of proto-punk. Perhaps not as "punk" as what is typically evinced (see: Sex Pistols and early Clash) but indicative of the spirit of punk...ever-restless. Not necessarily experimental or groundbreaking, but essentially free-spirited at its core.

Saturday, December 12, 2009

The Man #4: Tom Waits

When I refer to "The Man," I refer to titans in my music world. Perhaps later they will warrant their own "The Man" entries (as you may have noticed, I am terribly ineffective when it comes to maintaining series outside of "Record of the Moment"), but there are three people who currently rank ahead of Mr. Waits:

1. Jeff Tweedy

2. Bob Dylan

3. Lou Reed

and one who ranks behind:

5. Joe Strummer

Given that this is my current list, it is subject to flux. However (and this is a potential next entry if I get around to it), Jeff Tweedy will always be my number one. See my second "Records of Great Influence" entry here for the tip of the iceberg regarding the debt I owe Mr. Jeff Tweedy. Or, if you prefer Stephen Colbert's name for the guy, Geoffrey Velvet. The rest are obvious. Dylan, Reed, and Strummer are immutable figures in rock music, gods among mortals like you and I. But Tom Waits is the oddball in this group.

And that's the way I'd describe Tom Waits to someone if they had never heard of him. He is a total oddball. But he's also far and away one of the best songwriters in the 20th century and beyond. But beyond that there's a necessary chasm between "early Waits" and "later Waits."

"Early Waits" is the barroom, lounge music Tom Waits. Pretty jazzy, a little simpler, heavily piano-based. "Later Waits" is probably the longer, more prolific period of Waits. Heavily based in old-school blues, delighting in peculiar instrumentation, peculiar percussion rhythms, it's basically the darker cousin of "early Waits." My description of later Tom Waits would go like this, since otherwise my description doesn't help:

"Imagine like walking into a real seedy bar in like the 20's or 30's and there's some bar band playing some strange burlesque, vaudevillian music. It sounds familiar, yet because of the way it's constructed, it sounds like the bastard child of Howlin' Wolf and the Devil."

The most obvious thing, though, is the voice. Early Tom Waits maintains a light barroom croon that sounds youthful and full. Later Tom Waits sounds world-weary, war-ravaged, dogged by the devil; ranging from a sort of sinister growl to a furious and explosive roar.

But that is not to say that "early Waits" is better than "later Waits" or vice versa. It's more of a "which Waits do I want to hear right now?" and it's there. Boom. Early Waits? I'll put on Closing Time, his superb debut. Later Waits? I'll put on his landmark Rain Dogs, his Grammy-winning Bone Machine, or even put on his mega-package Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers, & Bastards. Or if I'm looking for a sort of "here is all of Tom Waits" sort of deal, I'll put on his most recent live record, Glitter and Doom Live.

Why is he one of "the Men"? Partially because he is such an oddball. How has the guy maintained a career playing this sort of music? Not because it's bad, because I love it all to death (or why else would I be writing this?). But commercially, it at first seems totally, totally suicidal. Totally anti-commercial, letting his music exist without being sullied by the post-industrial landscape that so often stains music through commercialism. It's a perfect recipe for disaster, when you look at the landscape now. Still, like the vagrants, the homeless, and the drunks that Tom Waits often writes about, he persists in spite of the changing tides of music. The man does what he wants, and that's one of the other things I love about him. Not about to bend to the will of any man. He plays what he wants. And, well, if you mess with him, he'll probably sue you too (Waits has a long history of suing people for wronging him). Well, if I messed with Tom Waits I'd probably deserve to be sued, too.

That's why I love Tom Waits. That's why he's my Man #4. This favorite quote of mine sums up Tom Waits extremely well, via Tom Waits himself:

"My kids are starting to notice I'm a little different from the other dads. 'Why don't you have a straight job like everyone else?' they asked me the other day. I told them this story: In the forest, there was a crooked tree and a straight tree. Every day, the straight tree would say to the crooked tree, 'Look at me...I'm tall, and I'm straight, and I'm handsome. Look at you...you're all crooked and bent over. No one wants to look at you.' And they grew up in that forest together. And then one day the loggers came, and they saw the crooked tree and the straight tree, and they said, 'Just cut the straight trees and leave the rest.' So the loggers turned all the straight trees into lumber and toothpicks and paper. And the crooked tree is still there, growing stronger and stranger every day."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)